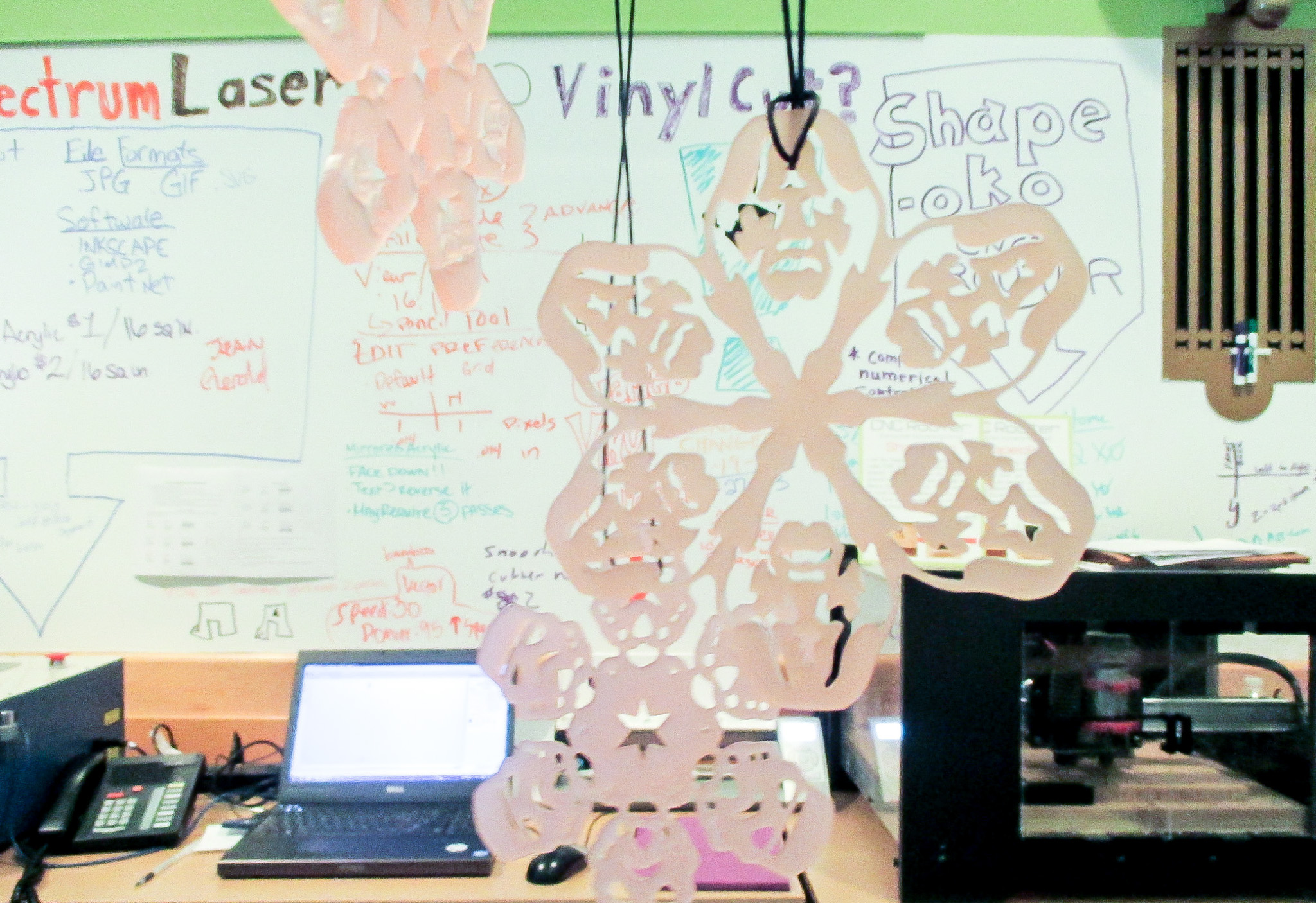

The subtle odor of melting plastic welcomes you to the Maker Lab at the Harold Washington Public Library in downtown Chicago. Whiteboards, rather than bookshelves, line the bright green walls. Librarians aren’t shushing patrons: people talk loudly over the low hum of 3D printers and laser cutters.

One of those voices belongs to Denise Bennem. She has been unemployed for four months. Bennem, 40, read about the Maker Lab when it opened in July and has been attending classes for the last few weeks. “I want to gain skills to find myself a hobby,” Bennem says. “I want to make something with my hands that I can show the world.”

So far she has learned to make laser-cut earrings and vinyl-decorated greeting cards. In the early evening of a Monday in November, she joined 10 other people in a class to learn how to make a laser-cut mirrored ornament.

Using Inkscape, free software for drawing vector images, she designs a snowflake. When she can’t rotate the snowflake, a man who has a bit more experience with Inkscape points her to the right tool. With the snowflake adjusted just the way she wants it, Bennem saves it to a flash drive and brings her work over to the laser cutter, where a library employee prints the designs.

These snowflakes created in the Chicago Public Library makerspace are from designs by Matters of Grey and Anthony Herrera.

She is one of many people across the country who are increasingly using libraries as a place to learn how to make things. This is in line with the mission of libraries to educate, but it also marks a shift from a focus on accessing knowledge to directly teaching people to create work. It’s a vision of what libraries will encompass.

“At the library, we introduce people to new ideas, new concepts through books and programs. [The Maker Lab] is introducing people to new technology through collaborative learning and creating that is hands-on,” explains Mark Anderson, chief of the Business, Science, and Technology division of the Chicago Public Library.

The Maker Lab has been a huge success. “It’s been crazy popular. We can’t keep up with demand for classes,” says Pedro Leon, one of the librarians who works in the Maker Lab. “People have been reading about technologies like 3D printers for a long time. This is giving them an opportunity to learn this stuff.”

Anderson hopes that the classes act as an “on-ramp for making.” He encourages people to use the skills taught in classes to work on their own projects during the open lab hours. He expects that some people might eventually become involved at more professional makerspaces in Chicago.

Amy Pariser, 29, is an interior design student, and had no experience with maker technology when she went to a vinyl-cutting class a few months ago. She has since been coming to the Lab once or twice a week to work on making a lamp and a sconce. She says that on a typical Saturday afternoon during the open lab hours there are about 15 people working.

During the Monday class, Arturo Duarte, 24, an engineering student, is prototyping a design in 3D for a pinhole camera. Roberto Lopez, 37, works on an LED sign by cutting shapes into acrylic with the laser cutter.

The Maker Lab is funded by a federal grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services. The grant ended in December, but the library received an extension to keep the Lab operating through March. Then the space, called at other times the Innovation Lab, will transform into something else. “Maybe a graphic design space or an e-reader petting zoo,” Anderson muses. It is a process of innovation and iteration that lets the Chicago Public Library experiment with new ways to meet patrons’ changing demands.

A study on library habits by the Pew Internet & American Life Project found that 59 percent of Americans definitely want libraries to have “more comfortable spaces” for working and collaborating. Forty-seven percent said libraries should definitely offer “more interactive learning experiences.”

Larra Clark, the director of the American Library Association program America’s Libraries for the 21st Century, explains that libraries have become “technological hubs” in their communities. Over the last decade the number of Internet-connected computers in libraries has doubled. Since 2003, the number of e-books in circulation has tripled. Programs to teach basic technology skills are available at more than 90 percent of public libraries across the country.

Makerspaces like the one in the Harold Washington Library are starting to pop up across the country, Clark says. They seem to be the next step in libraries’ transformation for the 21st century. “There is always an adoption curve,” notes Clark. “Part of that has to do with resources, leadership, and willingness to take risks. There are going to be different speeds of change, but we are starting to see this revving up everywhere.”

The Chattanooga Public Library created the 4th Floor, a 14,000-square-foot space that is part public laboratory, part educational space. Libraries also have high-tech makerspaces in Westport, Connecticut; Fayetteville, New York; and Fort Wayne, Indiana. The Madison Public Library created the Bubbler, a series of programs led by experts from the community that cover everything from animation to dance to clothing design. And last summer, the Washington, DC, Public Library opened up the Digital Commons, a collaborative workspace.

More and more people, like Bennem, who want to use expensive cutting-edge technologies will be able to do so with only a library card, rather than by buying a makerspace membership or their own gear.

While Bennem waits for her ornament to finish printing, she mentions she has learned enough to make Christmas gifts for her family. The library has given her the opportunity to create and give meaningful holiday presents.

A soft ding sounds. The laser cutter is finished.

Bennem carefully removes her snowflake ornament from the laser cutter. She slowly peels off the plastic protecting the mirrored part of the design and admires her work.

Photos by the Chicago Public Library.

Alex Duner is studying journalism and computer science at Northwestern University, where he is also a student fellow at the Knight Lab.