It’s dusk at Pickathon, the Oregon summer music festival famous for turning even the most uptight attendees into short-term hippies. My friends and I are sitting in camp chairs at a campsite in the forest, our home base for the weekend. On a stage in the middle of the woods, Neko Case jokes about how depressing her music is. Her easygoing persona is a welcome counterpoint to her self-excoriating songs.

A friend passes me his pipe. I haven’t smoked pot in years. When I smoke, I’m prone to paralyzing, near-hallucinatory panic attacks. But out here, surrounded by friends, with Case’s voice drifting through our campsite, smoking seems like the thing to do. I take a hit.

Forty-five minutes later, I’m still frozen in my chair. Onstage, Neko Case is riffing about having a baby made of butter. “My little butter boat,” she says. “My little butter boat baby.” Everyone laughs. I have no idea what’s going on. Eventually I crawl into my tent, and spend the next several hours locked into an endlessly regenerating spiral of anxiety and self-loathing. (Topics under consideration include the ultimate unknowability of other human beings, and whether or not it’s ethical to keep a cat as a pet.)

Twice I have to force myself to leave the relative safety of my tent and find a portable toilet. The campground, strung with lights, has the ambiance of a horror movie. I avoid making eye contact with other campers, who are clearly having much more enjoyable substance-use experiences than I am. “It’s just weed,” I tell myself. “No one has ever died from smoking weed.” I spend the night curled in a ball in my sleeping bag, and leave early the next morning.

I haven’t purchased marijuana since I was in high school in the late ’90s, and I still think of it as something you score in a parking lot off a squirrely kid in a puffy jacket. Back then, the worst consequence of smoking pot was the decision to use two Kit Kat “fingers” as chopsticks. (Read: There were no negative consequences.)

There’s a good chance the pot I purchased back then was weaker than the stuff I encountered at Pickathon. According to data gathered by the University of Mississippi’s National Center for Natural Products Research, marijuana potency has more than doubled since 1998 as measured by a sample’s percentage of tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC, the primary psychoactive component in cannabis.

Stronger pot might indeed be part of my paranoia problem, but there’s no reason it should stay a problem. The marketplace has changed considerably in the last decade and a half, with partial legality dramatically increasing information and options. The weed I found at Pickathon gave me a panic attack, but I might be able to find something out there that doesn’t.

Lousy names for legal scores

Medical marijuana has been legal in my home state of Oregon since 1998, and our neighbors in Washington recently became one of the first states to legalize it for recreational purposes. Like the 17 other states where medical marijuana may be legally prescribed, Oregon is home to a loose network of growers, distributors, and medical marijuana cardholders, all of whom cultivate and share institutional knowledge about marijuana. Throw the Internet into the mix, and the result is a surprisingly professionalized body of information about different strains of marijuana and their effects.

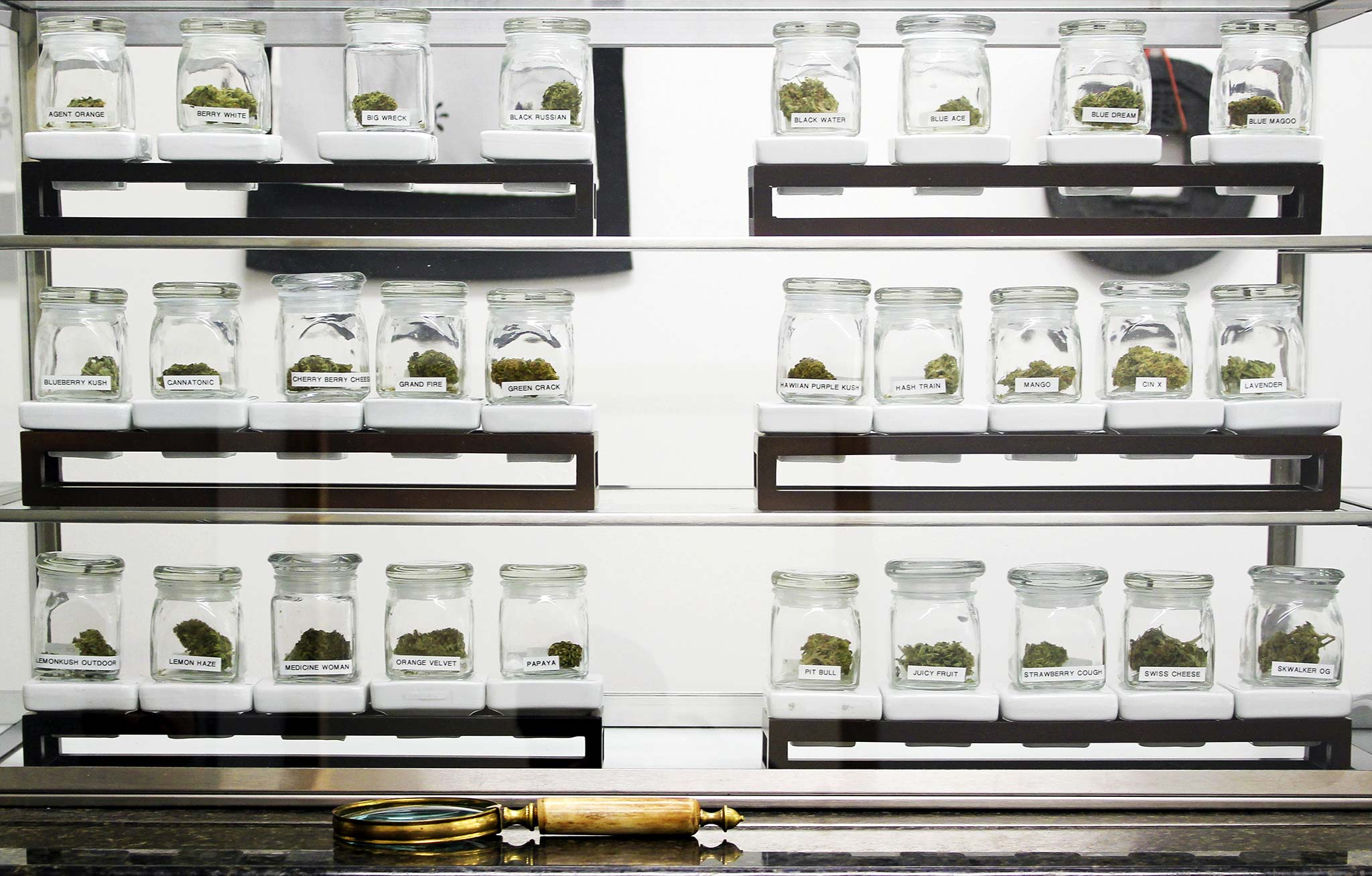

On a Saturday in early December, I visit the medical marijuana group known as the Human Collective.1 Housed in a business park just south of Portland, THC’s office resembles a naturopathy clinic, or perhaps a slightly stinky real estate office — there’s a reception area, a waiting room, and an inner office where neat rows of small, labeled jars sit in a small glass display case: Hash Train, Orange Velvet, Medicine Woman.2 There are also lollipops, butter, hard candy, and other edibles. (Or, depending on how committed you are to the terminology of medical marijuana, “medibles.”)

The collective’s director, Leslie Miller, is quick to tell me how much she deplores the lack of professionalism at many other marijuana clinics. “You walk in the door, there’s all these pot leaves and hippie images over the wall, things that just scream ‘hippie freakshow party,’ and all these farmers with big jars of marijuana that’s dispensed in little plastic baggies.” She shows me the opaque blue vials that the Human Collective uses, labeled with the strain (“Pit Bull,” for example) and Oregon’s medical marijuana statute. The message is clear: This is medicine — albeit medicine with some pretty stupid names.

On the wall hangs a poster created by Oregon-based chemistry lab Sunrise Analytics, which lists the chemical breakdown of 20 common marijuana strains. Every strain distributed through the Human Collective is tested for pesticides, mold, moisture content, THC, and CBD. (CBD, or cannabidiol, is the compound credited with many of marijuana’s medical benefits, including pain relief.) These variables reflect not only the purity and integrity of the product, but also the strain’s ultimate effect. “Someone who’s looking to party is gonna look for something high in THC and not care about CBD,” Lesley explains, “but from a pain standpoint, CBD is the way to go.” As someone who’s not looking to party, I make a note of this.

“Say I came to you because I’m prone to severe menstrual cramps, but pot makes me really paranoid,” I ask, struggling to sound as though my interest is purely academic. “What would you recommend?”

Miller swivels her computer’s monitor toward me and directs her browser to Leafly.com. The site’s design mimics the periodic table; it’s a chart in which each colored box corresponds to a cannabis strain. Users can search according to their medical condition (“nausea, pain, seizures), as well as by “effects” — traits like “focused,” “hungry,” “giggly,” or “lazy.” If you’re in a state where medical marijuana is legal, the site will even tell you where in your area to find what you’re looking for, and user reviews of each strain provide feedback.

(I previously considered Yelp reviews to be the absolute nadir of the Internet, but some pot reviews are even worse. Of a strain called Deathstar OG, one anonymous user writes [unedited]: “Loved this shit. Toked a bowl right before bed. Watched spongebob for about a half hour, then just laid in bed soo content. Imagination went wild. Loved it. Unfortunatley, i was pretty paranoid. I thought i kept hearing someone walk around, then I realized it was just my heart beating.”)

Miller checks boxes for PMS and anxiety, and the site suggests I might try a strain called Chocolate Chunk (ack!), which is available at the Rose City Wellness Center, just two miles from my house, for $10 a gram. I do the math for an eighth of an ounce, a quantity I understood during my pot-buying days as “the bottom inch of a plastic baggie”: $35. That’s $5 to $15 less than the going street rate in Portland.

Some of the most well-known strains, Miller explains, have been bred for decades. Others are hybrids, cross-bred to emphasize certain qualities, of which THC levels are just one variable. “From the grower’s perspective, they’re not growing pot for themselves,” she explains. “They’re artists when it comes to bringing out the best qualities of the plant.”

Your mileage may vary

Oregon medical marijuana cardholder Steph Castro uses pot for chronic pain and anxiety. She tells me that she seeks out strains recommended for their pain-relieving qualities, but that she tries not to be too “bourgie” about sussing out the finer points of each strain. (There are definite parallels between pot aficionados and, say, oenophiles.)

Certain differences from plant to plant are palpable, she says, primarily whether it’s a sativa or an indica. These are the two cannabis species most widely cultivated for consumption, and their effects are distinctly different. Sativas tend to be more uplifting — and anxiety producing, ding ding ding! — while indicas are more relaxing. Most individual strains (such as the lineup on display at the Human Collective) are either purebred sativa or indica, and others are a hybrid of the two. Plants are carefully crossbred to cultivate desired traits, and strains are propagated via either seed banks or cloning.

The best-known strains have global reputations — in fact, The Official High Times Field Guide to Marijuana Strains purports to describe all of the world’s top pot varieties. When it comes to the touted effects of individual strains, though, Castro notes that “there’s some power of suggestion going on. If you smoke some Blue Diesel, you know to expect that your senses will be enhanced.”

Earlier this year, a Portlander who goes by the name Ganja Jon placed first at Seattle’s High Times-sponsored medical cannabis contest, for the hash oil he produces and distributes to Oregon medicinal marijuana patients. He’s been involved in the medical marijuana community for years, both as a professional producer and an activist; he recently spent a week in Amsterdam, judging hash oil for this year’s Cannabis Cup. (He also once popped out his glass eye in front of comedian Brian Posehn.)

Ganja Jon’s a legitimate marijuana expert, and he explains that the Pacific Northwest is full of established, reliable strains — as opposed to California, where new and different strains crop up all the time. “Charlie Sheen gets popular,” he says, “and all of a sudden there’s ‘Charlie Sheen OG’ in all the clinics.” The older the strain — and some of them go back decades — the more agreement there tends to be about its effects. “If you look at a lot of classic strains, most people have the same opinions: ‘Jack the Ripper’s gonna get you really stoned, but it’s gonna keep you awake.’”

Crowd-sourced reviews are “great tools as a starting point,” Jon says, “especially for older patients who don’t know what ‘Strawberry Kush’ is.” But like the Human Collective’s Miller, Ganja Jon emphasizes that individual experiences will vary, and that the best way to learn about what works for you is to “talk to growers about what they’re growing” — something that’s increasingly easy to do, with the legitimization conferred by medical marijuana licensing.

Recreational marijuana is still illegal in my home state, but as of Thursday, December 6, I’m a 10-minute drive from enjoying the legal privileges afforded in Washington State. Washington’s Liquor Control Board has a full year to determine how pot will be regulated and distributed (at the moment, it’s legal to use, but not to purchase or sell).

Intervention from the federal government remains a possibility, as marijuana is still illegal under federal law, though President Obama recently noted that targeting recreational marijuana users in Washington and Colorado should not be a priority for the feds. Should the day come, however, when I can stroll into a Washington dispensary and legally purchase a strain of my choosing, I might take a chance on some Chocolate Chunk.

Photo of the Human Collective’s offerings by Pat Moran3.

-

Get it? ↩

-

You can view a small photo gallery of THC’s office at Flickr by Pat Moran. ↩

-

Pat Moran is a photographer from Portland, Oregon, whose work can be seen at patmoran.tumblr.com. He is also an actor, producer, and company member at Action/Adventure Theater. ↩

Alison Hallett is the arts editor of The Portland Mercury, an alt weekly in Portland, Oregon, as well as the co-founder of Comics Underground, a quarterly reading series that showcases Portland's thriving comic book scene.