Some high schools take field trips to zoos, museums, or national parks. My high school in Taiwan took us to a semiconductor fab.1 Our first stop: a display case, showcasing the evolution of the silicon wafer, from two to four to six and, finally, eight inches.

Our new eight-inch fabs are the most precise and advanced in the world, the tour guide boasted. Someday we’ll have twelve-inch wafers.2 By that time, he winked, maybe some of you will be working for us.

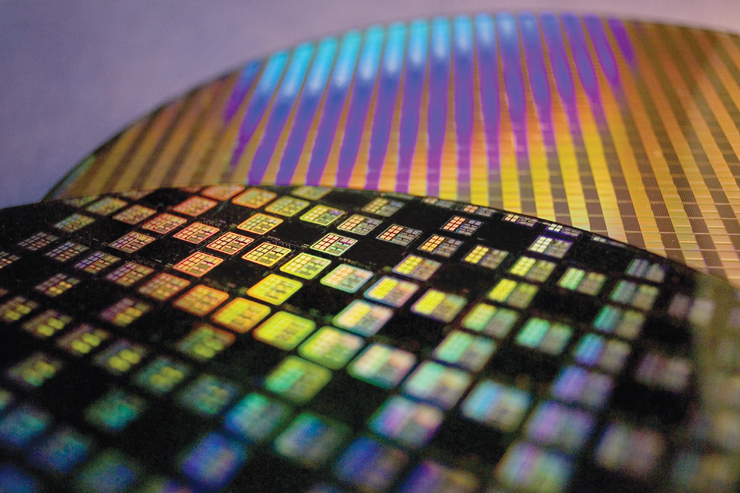

He paused, allowing us to admire the shimmering silicon wafers, often referred to as “Taiwan’s Gold,” a pun on the Chinese sound jin — a homophone both for gold and wafer. The wafers stood as an unabashed testament to the promises of technological progress, symbols of Taiwan’s economic past, present, and future.

Experimenting on students

I attended the National Experimental High School located in the Hsinchu Science and Industrial Science Park. Its name is no joke: we were literally a government experiment, an attempt to reverse the massive brain drain that dominated the intellectual, social, and political landscape of postwar Taiwan.

From the 1960s until the 1980s, flocks of highly educated, talented Taiwanese students emigrated to the United States. The majority of those students were college graduates in the fields of science and technology, with degrees in mechanical engineering, electrical engineering, civil engineering, physics, and chemistry, who went on to further studies in America as the opportunity for graduate degrees in Taiwan were scarce.

Very few of them returned after they got their degrees: 88% of Taiwanese students who migrated to the U. S. stayed there, because they got jobs either in universities or at tech companies like HP and Texas Instruments.3

Hoping to fight these trends, the government of Taiwan aggressively recruited Taiwanese talent with major tax breaks, incentives, and government funding. Modeled after the Stanford Research Park, the Hsinchu Science and Industrial Park, founded in 1980, was part of the government’s broader strategy. The government got its first major coup when it lured Morris Chang, who worked as a vice president with Texas Instruments, to return to Taiwan.

Chang’s strategy for Taiwan was a simple yet big gamble: rely on razor-thin margins to gain market share. He bet that Taiwan, with its strong foundation in plastics manufacturing, had a comparative advantage in cheap production. (Foxconn, for one, got its start in the 1970s making plastic TV knobs, before adding electronics.)4 Leave design to the Americans, he argued. We’ll focus on producing the stuff that they want.

With investments from the Taiwanese government, Chang launched Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), the first dedicated semiconductor foundry. Chang’s gamble proved to be a success: TSMC very quickly became the largest semiconductor plant in the world. Today, it has cornered close to 49% of the contract chip manufacturing market.

The government’s investment in the high-tech industry proved a success. Drawing on Chang’s model, Taiwan quickly became a major player — if not the dominant player — in the global semiconductor industry. This influence continues today: among the top 10 semiconductor foundries in the world, three are Taiwanese, and a fourth is based in China but was originally a TSMC production.

Bringing back brains

As a result of these changes, the brain drain was reversed. Scores of Taiwanese, who only a decade earlier would not have dreamed of returning to Taiwan, were inspired by optimism over an improving political and economic landscape to return home. (Americans may not recall that Taiwan remained under martial law through 1986.)5

My father belonged to this broader movement. Even though he had gotten tenure as a physics professor at Columbia University, he heard the call to return home to help build a more solid academic research environment. That same impulse brought back most of the parents of my friends. Many of them had cushy jobs at places like HP and Bell Labs before they returned to Taiwan.

The physical layout of the Park itself reflected the government’s attempt to cater to a Taiwanese populace that had grown accustomed to American life. Taiwan, an island, occupies an area slightly larger than Maryland, but has the second-highest population density in the world — Bangladesh is No. 1. Taiwanese live mostly in cities filled with labyrinthine streets, overcrowded with people, motorcycles, and bicycles. In contrast, the Park was the closest thing to a planned, suburban landscape that Taiwan could offer — and as antiseptic as the clean rooms of the fab.

In the Park, streets were straight, sidewalks were newly paved, and drivers obeyed traffic rules. Most of us lived in apartment blocks that reflected the style of large-scale governmental planned housing projects of the 1960s, but our apartments were generally bigger, more modern, and more comfortable than our Taiwanese counterparts. It was always a shock visiting some of my relatives, who lived in old, dilapidated houses, and were merrily crammed into shared tiny quarters.

Luring back émigrés

My school was a strategic weapon in the government’s emotional appeal to bring Taiwanese families back home. The school was designed so that returnees’ American-born children could continue to receive an American education and had their transition back into Taiwanese society eased. Class sizes were small, as enrollment was limited to the children of employees at institutions related to the Science Park.

I attended the school’s Bilingual Department (since renamed to this mouthful: the International Bilingual School at Hsinchu Science Park), which offered a curriculum that half followed the American model and half followed a Taiwanese model.

We Bilingual Department kids had a major advantage: we didn’t have to take the high-school entrance exams that the “normal” Taiwanese kids had to take, which meant that we were exempt from the incessant testing pressures that penetrated their daily life with ominous overtones of potential failure. We stood apart in other ways too: our clothes, our accents, our obnoxious, loud talking in English. We drew stares when we encountered the “normal” kids. They had contempt for us: we were the rich, snobby American kids who spoke poor Mandarin.

Technology was what kept us connected to America, a place that, with every passing year, seemed at once farther distant yet familiar, and a place that many of us still considered our real home. It was technology that allowed us to retain our “American” upbringing, or what remained of it.

Computer games played a large part in this experience: we shared notes about adventure games like Monkey Island, Gabriel Knight, and Quake. We watched American movies (The Rock was a perennial favorite), and listened to American bands like Weezer and Green Day. In the late 90s, we all joined ICQ, and we started chatting online with friends who had moved away, often back to America.

By then, technology allowed us to stay on top of the cultural trends of America, so that by the time I entered college in the states, I did not feel so disconnected from my American friends. (One of my first college experiences was bonding with friends by watching 10 Things I Hate About You and other teenage rom-coms.)

But in other ways, the school inherited the particular cruelties of the tech market as our parent’s world was never distant from ours. Our classroom reflected the turnover and constant mobility of the industry: many of our friends stayed for only a couple of years and then moved to wherever their parents found a new job. There is a certain culture surrounding technology that encourages a Darwinian view of the world, which can have a pernicious effect on a young person.

Parents, who knew intimately what it took to be competitive for college entrance boards, pressured us to achieve and perfect our SAT scores. The winner-take-all mentality of the tech industry wound its way into constant competition over grades. There was a natural hierarchy of subjects worth studying, with electrical engineering at the top. The study of literature and the humanities was viewed with a sense of bemusement and befuddlement. The expectations of highly-educated parents proved to be suffocating: people who didn’t do math or science were seen as weak and feeble-minded.

Tech’s false promise

Growing up in Taiwan, technology was both a source of deliverance and bondage. We knew its importance: we were reminded by cheery tour guides of its transformative power. It helped us transcend our daily lives, allowing us to make connections with a place that we imagined as home. The majority of us remain tied to the tech industry. (My best friend works at Flipboard, and I have friends who work at Facebook, Google, and eBay.)

But for some of us, the lure of remaining in the tech world was a poisoned chalice, a constant reminder of failed expectations, a world of pigeonholes and strictures. Many of my friends, who had the talent and inclination to become musicians, artists, poets, or writers, were never encouraged to pursue those paths; instead they were admonished for their lack of rigor and levity, and they never developed the courage to follow their passions.

I have retained my love for technology. I can’t shake the gadget geek in me. And without the science and tech industry, my father would probably never have left Taiwan to pursue education in the States. Taiwan would not have the high standard of living it enjoys today had it not followed its path of development. But I can see that while it brings great wealth, the wealth has not undone the cultural assumptions and hierarchies in the country, and in some cases has exacerbated the idealization of wealth and power and social inequality.

Technological utopians claim that advances in science and technology will inevitably lead to the liberation of the individual person from the shackles of society. While that may have been true for some of my classmates, for others the tech world led to a narrowing, rather than a broadening, of their intellectual horizons.

When I arrived in New York for college, I found a different world. I went at my own pace. I made deliberate choices regarding what I wanted to study. I considered music, I considered religious studies; I settled on European history. These choices reflected also a culture that I finally felt I could leave behind.

Image courtesy Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., Ltd. Thank you.

-

A semiconductor “fab” or fabrication plant is where circuit designs are translated into silicon and thence into chips. New plants now cost billions of dollars. ↩

-

That day arrived in 2000, but the expense has meant a slow rollout. The Taiwan government just approved a fab that will use 450mm (“18-inch”) wafers, although it may be five years before all the technical details are worked out. ↩

-

The 1965 Immigration Act in the U.S. allowed “people having special education and skill qualifications” to bypass quotas. Prior to 1965, there were national quotas, set at a meager 100 visas each year for Taiwan. The act opened up the floodgates for Taiwanese immigration: Taiwanese scientist immigrants increased from 47 in 1965 to 1,321 in 1967. ↩

-

Foxconn remains a Taiwanese company even though its operations now are largely in China, although it has increased investments lately in other countries, like Brazil. ↩

-

Defeated in a civil war with the Communists, the Chinese Nationalists (Kuomintang) fled to Taiwan in 1949. They planned to use it as a base to relaunch and recapture the Chinese mainland. For decades, the Kuomintang, backed by the United States, maintained that they legitimately represented all of China. The Nationalists imposed martial law when they relocated to Taiwan and suppressed native political opposition. ↩

Albert Wu is a graduate student in history at University of California at Berkeley. When not thinking about European missionaries in China, he tries (and fails) to keep up with the latest trends in technology.