One day during his senior year of high school in Wilmington, Delaware, Rich Pell stayed after school to watch a spider get “silked.” His school was near the headquarters of DuPont, the global chemical company with the motto, “The miracles of science,” and his biology teacher was friends with an employee.

Scientists had identified the genes that made up the golden orb weaver’s silk, considered one of the strongest natural proteins found on Earth. They ultimately intended to produce large quantities of dragline silk, the strongest fiber among several kinds that a spider spins for webs, eggs sacs, and insect wrapping. Four of the orb weavers were in Pell’s classroom, on loan from DuPont’s Experimental Station.

That afternoon, Pell watched a visiting scientist tape the legs of a spider to a table and attach a piece of its silk to a battery-powered spindle, which collected the silk as the spider produced it. He remembers that as a weird window into the world of biotechnology.

Nearly two decades later, Pell has come full circle back to those spiders, this time via the guts of stuffed goats.

Living history

The route to the Center for PostNatural History takes you down Pittsburgh’s potholed Penn Avenue. The road passes through a series of neighborhoods in varied states of decay and repair: a swath of brick houses crumbling on one block, a modern glass-and-steel complex on the next; a fancy Mexican fusion restaurant on one corner, a series of shuttered doors and windows on the next.

It’s easy to miss the center: its facade is tucked between a chain pizzeria and a Vietnamese restaurant. It has the bland look of an architecture firm with the same outward-facing appearance of sterility. The curators describe it as a “public outreach center that examines the changing relationship between culture, nature, and biotechnology.” But it’s chock-a-block with bric-a-brac.

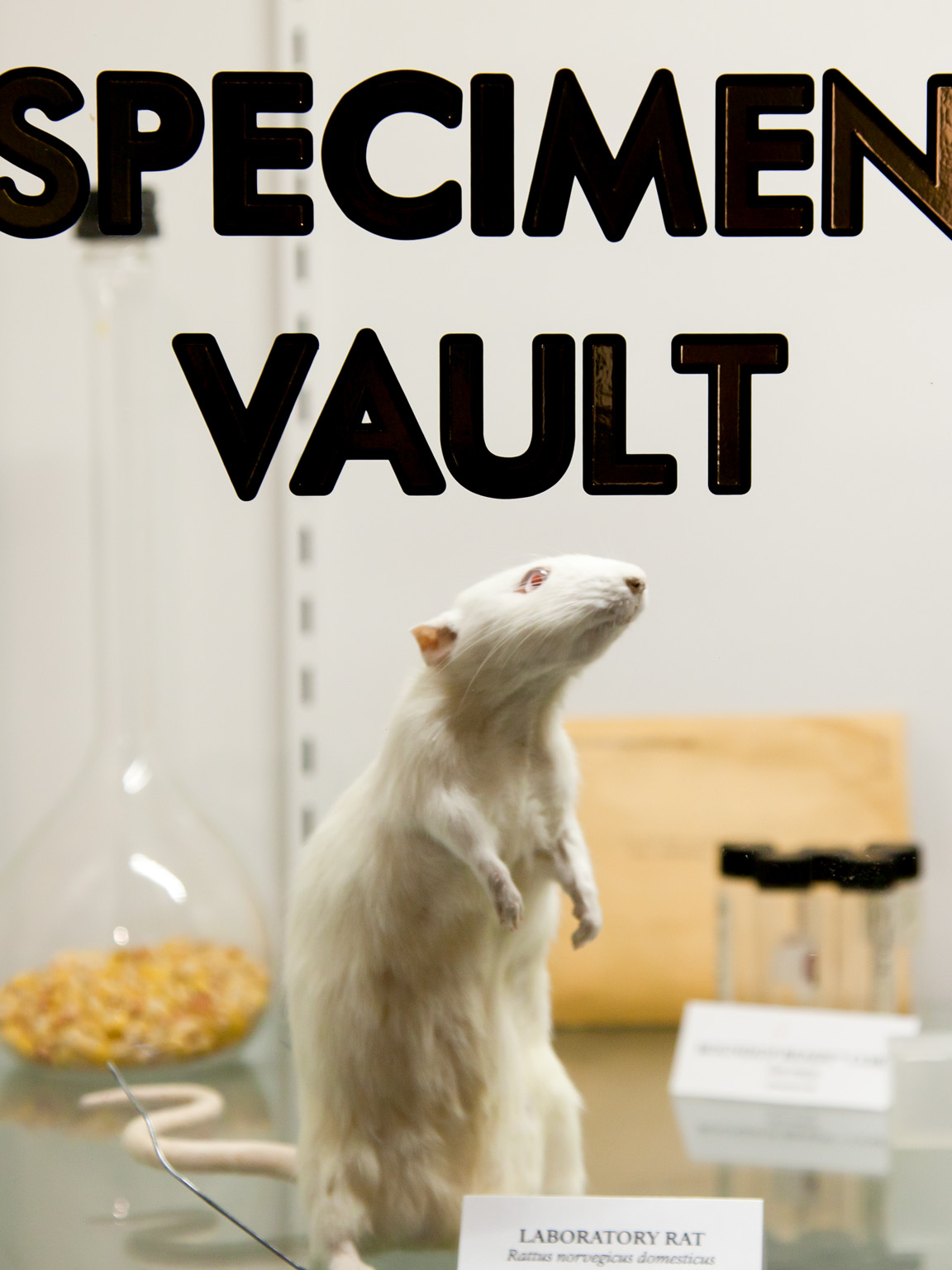

On entering, a visitor is confronted by a glass case with dog skulls on one shelf, a row of Sea-Monkeys packets on another, and specimens preserved in jars; a row of empty vials on the front windowsill labeled “Seeds from a Seedless Watermelon”; little charts on the wall detailing genetically modified corn; a small table with chairs with little pamphlets on it; and a pen-and-ink drawing of a screw-worm larva on the cover.

An enormous print covers one wall. At first glance, it seems like some sort of tripped-out painting. In fact, it’s a stereoscopic print of a pheasant embryo. The embryo is only a centimeter or two across, and the enlarged photo reveals — with a little explanatory help — that the bird underwent a botched genetic experiment, which was why it had only developed one eye.

Pell, the Center’s founder and co-curator, greets me from behind the counter. He is a bearded, intellectual-looking fellow in his late thirties. He smiles politely at each visitor, chirping, “Welcome to the Center for PostNatural History! Have you been here before?”

Richard Pell and Lauren Allen, the curators.

Breeding competition

Pell defines his museum’s purview to include any living organism that has been intentionally altered by people at any time in its history. More specifically, its reproductive life was manipulated. “In that blurry line of domestication is when postnatural begins,” Pell explains. This period began most extensively at least 10,000 years ago when humans started selecting animals with particular traits as pets or livestock.

“The thing we pay most attention to is when humans insert themselves into the reproductive life of another species,” Pell says. Take chihuahuas: they never would have made it in the wild. Postnatural organisms are the result of humans deciding which ones will and which ones won’t breed. “We’re continually creating things based on what we desire, what we fear.” Pell thinks of postnatural organisms as “cultural works.”

Before he became interested in the postnatural, Pell, an artist who currently teaches in the electronic media department at Carnegie Mellon University, worked with an artist collective called Institute for Applied Autonomy. The robots they created led him to synthetic biology, which in turn revealed what he saw as a “blind spot” in the documentation of biological and cultural history.

The Center for PostNatural History opened 18 months ago, after six years of research and specimen collecting. Co-curator Lauren Allen, Pell’s partner in life as well, is a Ph.D. student studying Learning Science at the University of Pittsburgh. Pell has always been interested in the collision of art and science; Allen is interested in how people take up and process scientific information.

The museum avoids taking a position or even presenting a debate. This lets you walk through the displays remaining oblivious to the fact that the circumstances surrounding an exhibit are controversial. I can gaze in a sort of fascination as Sea-Monkeys flit around in their murky vial of water. But when I read about their inventor, Harold von Braunhut, and how he had ties to the Aryan Nation, a whole new layer of complexity is added.

“Some people really embrace this idea that there’s this place that’s giving information about something that is controversial and not feeding you an opinion about it,” says Allen. Others find it very uncomfortable.

When constructing their exhibits, Pell and Allen try to refrain from using any language connected to academia, industry, or activism, which might create expectations in the viewer. Their goal is to simply tell the stories of the organisms.

As we chat, a handful of visitors wander into the sunny entrance of the museum. Some look a little confused. At one point a man walks by outside and pauses to look at the jar of seedless watermelon seeds. When he looks up, Allen waves at him, motioning him to come in, but he looks away and keeps moving.

“There [are] a lot of people who will peek through the window,” Allen explains, “and we’re like, ‘Come on, come on, come on,’ and they’re like, “Eh, we’re going to get Vietnamese food!”

Billy goat grapple

Pell never forgot the spiders he first encountered in his Delaware classroom, and they will soon make an appearance in his museum — but not in anything like their original form. Orb-weaving spiders leapt the genetic chasm, and now fit into Pell’s rubric.

In the 1990s, Randy Lewis, an academic, determined how to clone silk genes from spiders. A Canadian company, Nexia Biotechnologies, was formed and licensed some of his work and extended it. They spliced spider-derived genes into goats — picked for ease of breeding and docility — which would then express some of the proteins into milk. These proteins could be extracted and spun into a material dubbed BioSteel that would potentially be stronger than steel.

But the process of filtering the proteins and assembling the milk by replicating the chemical and mechanical process that occurs inside spiders into dragline and other kinds of silk was more complicated and expensive than Nexia anticipated. Despite raising a large herd of goats on a decommissioned Air Force base in Plattsburgh, New York (chosen for its isolation and security), the company shut down operations, euthanized many of its goats, and relocated its remaining animals to Canada.

Nexia’s diminished BioSteel herd was eventually adopted by Lewis, who took some long drives to pick them up in 2008 and 2009.1 He is now carrying out his research at Utah State University. Lewis is pursuing both transgenic goats and silkworms for biologically produced artificial tendons and human skin and tendon replacement. His lab created a shocking demonstration of bulletproof human skin in 2011 not intended for production, but to show a remarkable use of transgenic technology.

Two weeks before his museum opened in February 2012, Pell was interviewed by Nature. One organism he wishes he had, they asked? The BioSteel goat. It is a “poster child organism” for postnatural history, he tells me.2 Pell didn’t think he could get one because genetically modified goats are technically food animals, and regulations require that their meat be kept out of the food chain.

Two weeks after the Nature interview appeared, Lewis called him. “I have some of those goats,” Lewis said. He and Pell quickly agreed to figure out how to get a goat for the museum after one had died. The goats live out a natural lifespan, Lewis tells me by phone after my visit to the center. They are euthanized only if they develop a serious health problem (such as cancer or lesions) to which this breed is prone — whether genetically modified or in the breed’s original form. Lewis says while he can’t provide a complete animal, he and Pell were able to obtain a waiver from the FDA as the goat couldn’t possibly be used for meat after being handled by a taxidermist.

Pell explains as we sit in the museum foyer that “I’m waiting for that to happen.” He points to a space occupied by an AquaAdvantage salmon over the curtained threshold that leads to the museum’s main exhibit room: Hall of PostNatural History. “It could fit right there.”

Animal testing

Of the visitors who come through the door during my visit to the museum, one is a geneticist who studies pain and itch. A couple of veterinarians wander in; they have particular interest in the Rottweiler skull on display over the Sea-Monkeys packets because they’ve witnessed the genetic debilitation that inbreeding caused in purebred dogs.

Whenever Pell offers to answer any questions, many visitors just shrug and shake their heads, smiling bemusedly as their eyes scan the walls, fixing on the jar of albino snakes in formaldehyde here, an X-ray print of a ribless mouse skeleton there. For most people who push through the glass door, he simply explains that it’s a self-guided tour, and that if they proceed past the gray curtain that hangs in the exhibition space doorway, “The green button on your left will get you started.”

Behind the curtain, there’s a narrow passageway in which my eyes adjust to the dark as a voice narrates what postnatural means: nature, culture, and biotechnology as a small screen projects a series of antique drawings of horses, chickens, and corn. Somewhere beyond the brief passage, the room opens up, and white light flickers across the ceiling.

A panel on the left shows impaled fruit flies, and in a dark recess is a small fish tank with a few, faintly glowing GloFish — zebra fish that have a gene added so they glow in the dark. (The GloFish is commercially available, and so the museum can have live subjects.) To the right is a glass cube on a pedestal displaying a mounted Silkie chicken. A small plaque explains that Marco Polo described this breed of chicken in the 13th century, although it’s believed it originated much earlier than that.

In the main room, the source of the flickering light becomes apparent: 1940s footage of white lab rats undergoing experiments is projected against the wall. Three hungry rats in a glass cylinder tumble over one another after a piece of food. The footage plays on a loop, and the dry, scientific explanations are underlaid with an irony I can’t quite place.

Constantly evolving

In early museums, science and art were mixed together under one roof. By the 1600s, a jumble of nature, art, science, and fraud were regularly exhibited as curiosities, each presented with the same degree of credulity and importance, in “cabinets of wonder.”

It wasn’t until the Enlightenment where science became codified, the rational valued over the emotional or fantastical, that collections started to become divided. Lawrence Weschler, the author of Mr. Wilson’s Cabinet of Wonder, credits thinkers such as Galileo, Newton, Spinoza, and Descartes, for the “simple, straightforward advances in positivist certainty.” (See “Through a Glass Darkly” in this issue to read Nate Berg’s look at the eponymous Mr. Wilson and his Museum of Jurassic Technology.)

The way our institutions are modeled now — like Pittsburgh’s several Carnegie museums — science and art are separate but equal. And then they are separated further: technology from natural history, and art divided up into periods and styles.

The Center hearkens back to those less empirical days, although unlike the Museum of Jurassic Technology (which blurs reality) and the original cabinets (which lacked modern scientific rigor), both Pell and Allen are very firm on the fact that they never manipulate exhibits. They want their information to be as reliable as a traditional museum. That’s part of their purpose: to demystify organisms that are difficult to understand (BioSteel goats), that we haven’t thought of in a particular way (chickens), and that have a lot of baggage attached to them (lab rats). So yes, their purpose is to simply inform.

But Pell and Allen’s collection also fascinates, and some viewers will feel compelled to judge: is this good or bad? Even though there is no clear answer, it’s impossible not to feel compelled to try. “Our main job here is not to convince you of position,” Pell says, “but to make you reconsider your own. Whatever it is.”

Visitors will soon be able to form their own opinions about goats with spider genes. After years of coveting such a goat, Lewis let Pell know that a goat had met its maker and was available. Rather than a complete goat, the center will get just the skin, which is currently at a taxidermist’s shop being stuffed and sculpted.

Pell and Allen will pick up the goat from Lewis in Utah in a few weeks, and it will be a reunion of sorts: Pell will get to meet living genetically modified goats, too, that contain the genes of the spiders that helped inspire him in the first place.

Rat photo courtesy Center for PostNatural History. Curators photo by Stephanie Strasburg.

-

Nexia isn’t technically out of business, even though it more or less doesn’t exist in any substantial form. A quasi-governmental Canadian agency now seems to own its patents and licenses, according to Lewis, who negotiated with it to get the goats. Nexia sold one drug before it shut down goat operations (related to nerve-gas vaccination and also involving goats), and went through a merger with an energy company that let the latter become a publicly traded company using Nexia as a shell, a common and legal tactic. ↩

-

In our interview, the Nature interview, and in many other places, including this video and the museum’s Web site, Pell repeated a story that he thought was accurate: that the goats had been acquired by the Department of Defense or its Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. There was some military assistance and interest in Nexia’s early work, including help with an academic paper, but the United States government never owned any goats nor has any now. Pell is now aware of the details. ↩

Amanda Giracca received her M.F.A. from the University of Pittsburgh and now writes from the Berkshire hills of western Massachusetts. Her writing interests range from phantom catamounts to aurochs to the anatomy of the face, and her most recent work has appeared or is forthcoming in Fourth Genre, Terrain.org, and Flyway. She is also a regular contributing writer and editor for Vela Magazine.