In Terry Kilby’s drone workshop

Around Baltimore, Terry and Belinda Kilby are considered ambassadors of unmanned aerial vehicles, better known as drones — a result of their having designed, built, and flown their own line of multi-rotor drone-copters, starting in 2010. “We get emails every day from people asking us how to do this,” Terry says.

Today the duo is known as Elevated Element, and what began as an art project to photograph from the air the monuments and landmarks of Baltimore has become a quickly growing commercial drone imaging business. Local real estate firms, outdoor music festival planners, and even a 3D-scanning company have asked for Elevated Element’s drones to take photos and video from the sky.

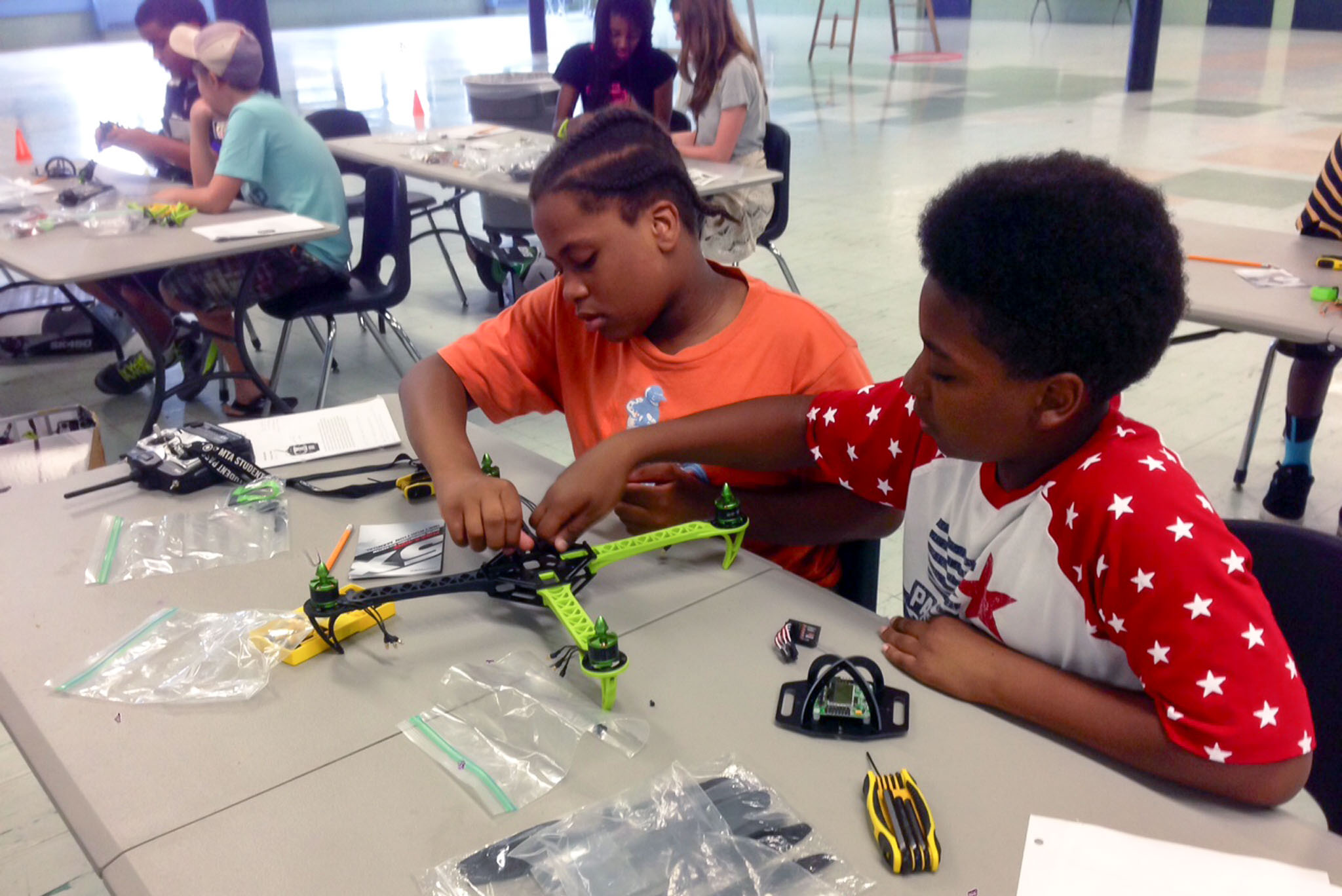

One can find civilian drone operators in most cities offering similar services. But the Kilbys have set sight on a new audience: they are taking their technology to the students of Baltimore. Drawing on Belinda’s 10 years as an art teacher in Baltimore’s public schools, the couple taught a two-week camp this summer at the downtown nonprofit Living Classrooms, guiding middle school students through the assembly and basic flight maneuvers of their own quadcopter drones.

“We hope that the kids we teach are going to come up with ideas that we never even dream of,” says Terry.

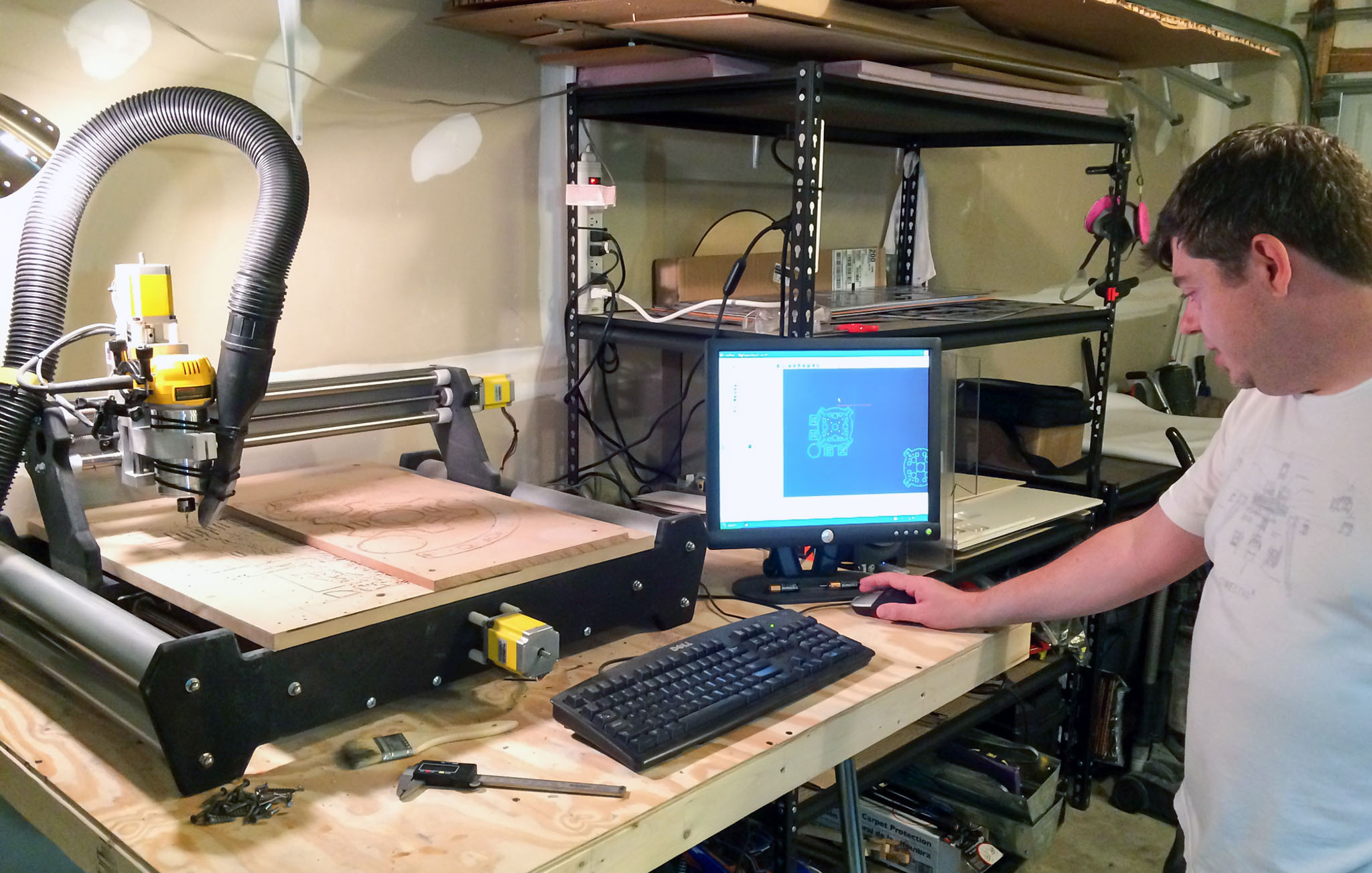

Terry Kilby fires up the CNC machine at his garage-turned-workshop.

Flights of fancy

Though Terry Kilby, 41, grew up playing with remote-control (RC) cars, he left those behind with his childhood and became a software engineer. In the early 2000s, while working at a startup, he created speech-recognition software that transcribed and indexed AM radio station broadcasts. Senator Barack Obama, who wanted to know which AM stations were talking about him, was an early client, Terry says.

He’s now an iOS developer for KPMG (formerly Cynergy), developing health care apps and devising products that use Leap Motion sensors. It wasn’t until 2010, the year he and longtime friend Belinda started dating, that his boyhood fondness for RC came rushing back.

Terry received a little RC car as a groomsman’s gift at a friend’s wedding that year. Shortly afterward, he bought an RC helicopter “and a bigger car and another helicopter and another helicopter,” Belinda says. The two purchased a keychain camera, attached it to one of Terry’s helicopters, and flew it around the 14-foot-high rooms of their apartment in Baltimore’s Bolton Hill neighborhood. A nonplussed Boo Boo, their all-white cat, was the Kilbys’ first subject.

“We were doing that purely as a joke,” Terry says. “But Belinda, being the artist that she is and having the background in art that she does, saw those really crappy photos — those grainy, low–resolution photos — and could see past the imperfection.” “I wasn’t even thinking about building at that point,” she says. “I just said, ‘Is there any way you could carry a better camera?’”

The timing was perfect. An online, open–source movement behind personal drones was picking up steam alongside a hobbyist, mini-manufacturer impulse that arose from easier and cheaper access to 3D printers and CNC routers. And then the GoPro camera came on the market, intended originally for people to wear while playing sports or engaging in extreme activities.

Terry’s first copter was a crudely built three–rotor chopper made from pieces of wood he cut using a jigsaw in their apartment building’s shared laundry room. For subsequent drones, Terry hacked together flight controllers using an Arduino board and a makeshift gyroscope and accelerometer fashioned from the sensors ripped from Nintendo Wii controllers.

“There was no real flight controller at this point,” he says. “Each arm tried to stabilize itself and wasn’t aware of the others. There was a lot of wobble in the early days.”

Belinda Kilby prepares the Sirius SK4 for its next photography assignment.

Point and shoot

Four years and roughly a dozen designs later, the Kilbys’ drone-copters are much improved and as good as — maybe even better than — the DJI Phantom 2, one of the more popular models sold in stores as a kit for beginner drone pilots. Three different drones, each with a name that pays homage to the stars, constitute Elevated Element’s current fleet: the 10-inch-across Little Dipper, the 31-inch-across Cygnus, and the colossal Sirius, the same breadth as the Cygnus but weighing 10.5 pounds and equipped with eight 17-inch-long propeller blades.

Each is built in the Kilbys’ bi–level home about 20 minutes outside Baltimore. Three workstations are set up in the basement and garage, where batteries, propellers, 2.4 GHz wireless flight controllers (the same used for RC model airplanes), and sheets of carbon fiber and balsa wood are stored. A CNC router wired up with a desktop computer serves as Terry’s design station when it comes to cutting the frames of the drones.

He begins with the payload, which is usually a GoPro or DSLR camera that hangs from a gimbal fastened to the underside of a drone-copter. All of Kilby’s drone-copters are built around the object they are intended to carry. Next, the length and number of propeller blades, derived from a series of automated calculations performed by the online eCalc multicopter calculator. After that, the size of the battery, generally an 8,000 or 5,000 watt cell. The material for the frames varies by design, but carbon fiber is usually chosen.

When construction is finished, Terry ends up with something like his Sirius X8, a drone capable of flying for 24 minutes while snapping photos with a DSLR camera pivoting left, right, up, and down on a three-axis gimbal.

“I used to call his designs and builds the other woman,” Belinda says. “And then little by little I got more involved.”

Flying involves both Kilbys, who start at sunrise, when fewer people are out and about, to minimize any risk in case a copter crashes.1 A ground monitor gives Belinda a view of the object they’re shooting. She controls and triggers the camera while Terry — either by sight or with FPV (first-person view) goggles — commands the drone. Flights and shoots, like capturing the image of George Washington atop the 178–foot Washington Monument in midtown Baltimore, are planned out via Apple Maps.

During flight, Belinda issues simple commands — up, down, turn right, yaw left — until Terry has properly positioned the drone, and then she begins taking 400, 500, 600 photos — enough to ensure a handful of quality results. The pair released their first book in 2013, Drone Art: Baltimore, featuring photos their drones have taken of the Francis Scott Key Memorial, Inner Harbor, Penn Station, and other Charm City sights.

Baltimore city middle-school students assemble their own quadcopters during a two-week camp this summer.

The next generation

The FAA’s official stance is that commercial use of drones must be licensed, and they haven’t given approval for any use except in the Arctic. It was only this March that the Kilbys began taking on commercial work, after a federal judge ruled that the FAA couldn’t fine a drone-photographer $10,000 for being paid to film the University of Virginia, because the FAA had never opened up its commercial drone rules to the public for comment. The FAA is under a legal mandate, signed in 2012, to figure out how to allow appropriate use of drones by 2015, but that deadline is already certain to be missed.

So Elevated Element continues on, bringing drone photography to a younger generation of Baltimore makers. In July, Belinda led a class of 12 junior high students as they split into teams of two to build and fly quadcopters, relying on the off–the–shelf Turnigy SK450. Belinda describes the Turnigy as an easy, “plug–and–play” kit. If motors were spinning in the wrong direction, students had to figure out how to switch the corresponding ESC wires.

Prior to their first flights, Belinda demonstrated how to calibrate the basic four-button flight controller to ensure level flying. “We kind of view them as our apprentices,” she says. “I feel confident they could actually compose some shots.”

At its core, the drone technology is in service to the aerial art the Kilbys produce. Belinda says that good art not only pays homage to the past, but also takes artists and art lovers in new directions. In Elevated Element’s case, the sensibility is a literal one. And wherever Terry’s imagination takes him on his next custom-built drone, Belinda will be there saying yaw left.

Photos by the author.

-

The Kilbys say their safety record is impeccable so far: no crashes. They maintain the FAA-required flight ceiling of 400 feet, and, as is also mandated, their drone-copters return automatically to the point of origin if line-of-sight contact is broken. ↩

Andrew Zaleski is a freelance journalist based in Philadelphia. He is the former lead reporter for local technology news site Technical.ly Baltimore.