John Young by Henry Casselli

In March 1962, when NASA was still a toddler instead of the card-carrying member of the AARP that it is now, NASA administrator James Webb created the NASA Art Program. He wrote, “Important events can be interpreted by artists to give a unique insight into significant aspects of our history-making advances in space.”

The list of artists he selected reads like a walk through a Smithsonian gallery: Rauschenburg, Warhol, Rockwell, Wyeth, and Calder, among others. This group followed the growth of NASA from the early Mercury program through Gemini and then the moon landings of Apollo.

After Apollo, painters such as Henry Casselli continued the project, capturing events such as Columbia lumbering into the sky for the first time. Casselli’s watercolor “When Thoughts Turn Inward” depicts astronaut John Young on that day, April 12, 1981. Young looks focused, determined, and almost melancholy as he suits up for his mission. Viewing the painting, I can almost hear Young’s thoughts:

It’s here. This is it. This is the time.

But, as with most programs that do not involve blowing things up, funding for the arts has dwindled, leaving folks like Nate Parsons, my colleague at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab, to maintain the bridge from art to science.

The marquee of the Patterson Theater

Walking on sunshine

Nate and I stand outside the Patterson Theater in the Highlandtown neighborhood of Baltimore. Its vertical sign, the only one of its kind remaining in the city, is outlined by 940 fist-sized bulbs. It’s a reminder of the long-shuttered movie houses and theaters in this and other neighborhoods.

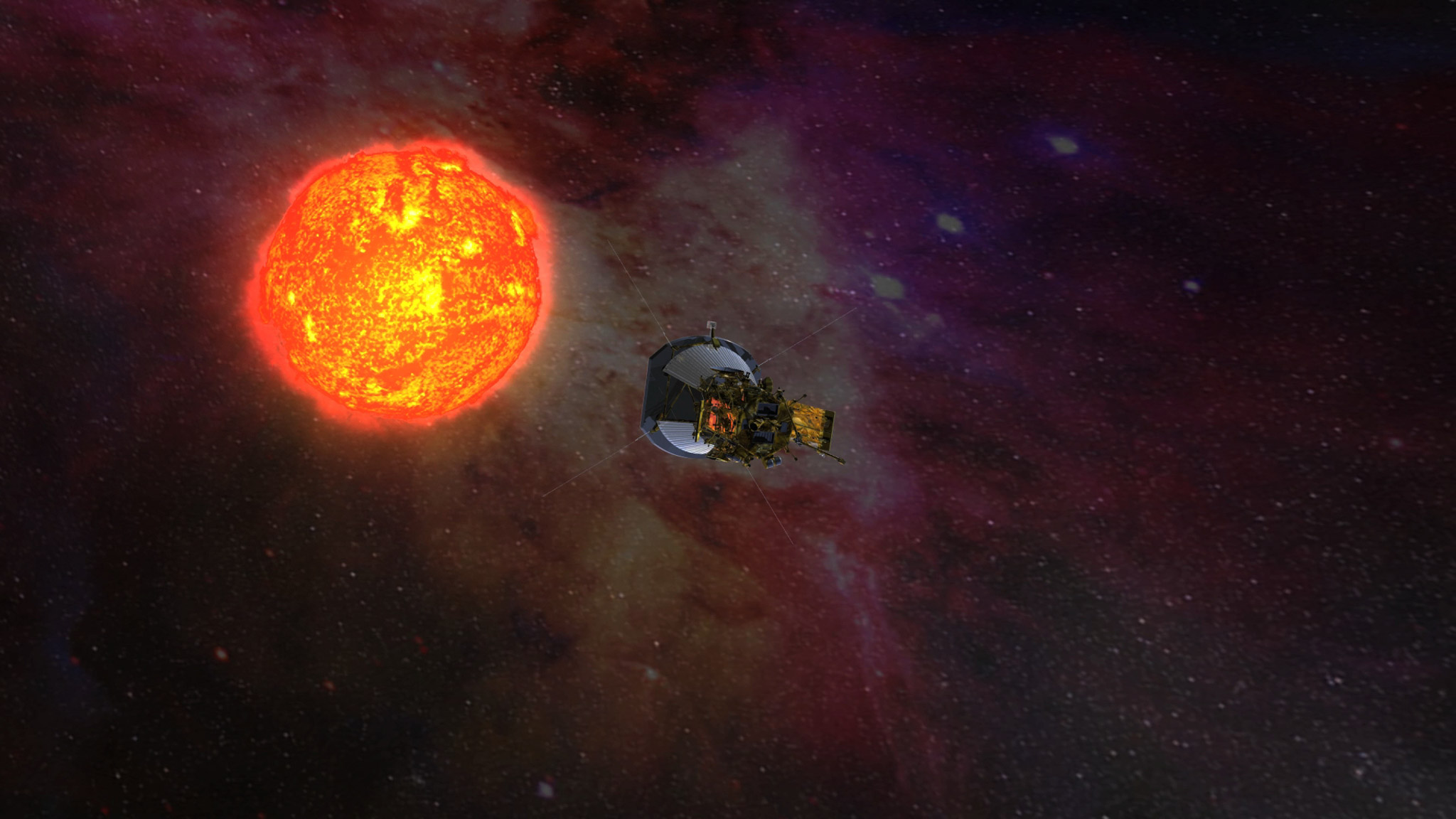

Tonight the theater hosts a local collaborative modern dance company called the Collective, a group that is in residence a short drive away at Bryn Mawr. The Collective is performing two acts of community-commissioned pieces called Tailor-made SHORTS. The closer for today’s performance is inspired by my current spacecraft mission, Solar Probe Plus.

Nate commissioned choreographer Lauren Withhart to use our spacecraft as the spark for a five-minute piece. We like to call Solar Probe Plus “A Mission to Touch the Sun,” because the vehicle will fly closer to our star than any mission before. And quickly too: at closest approach, the spacecraft will scream by the sun fast enough that it could take me from Baltimore to Philly in one second.

I watch as the Collective’s 13 dancers perform to a nearly sold-out crowd. Seeing their graceful moves, which would quickly throw out my 47-year-old back, I am reminded that it doesn’t take an Under Armour commercial to see that dancers are athletes.

Act 1’s pieces range from the serious Awe, or The Other, a reflection on a Rilke poem, to the humorous finale, #thesebitchescandancemakingfunofselfie. As the performers leave the stage for intermission, Collective selfies start popping up on the phones of audience members.

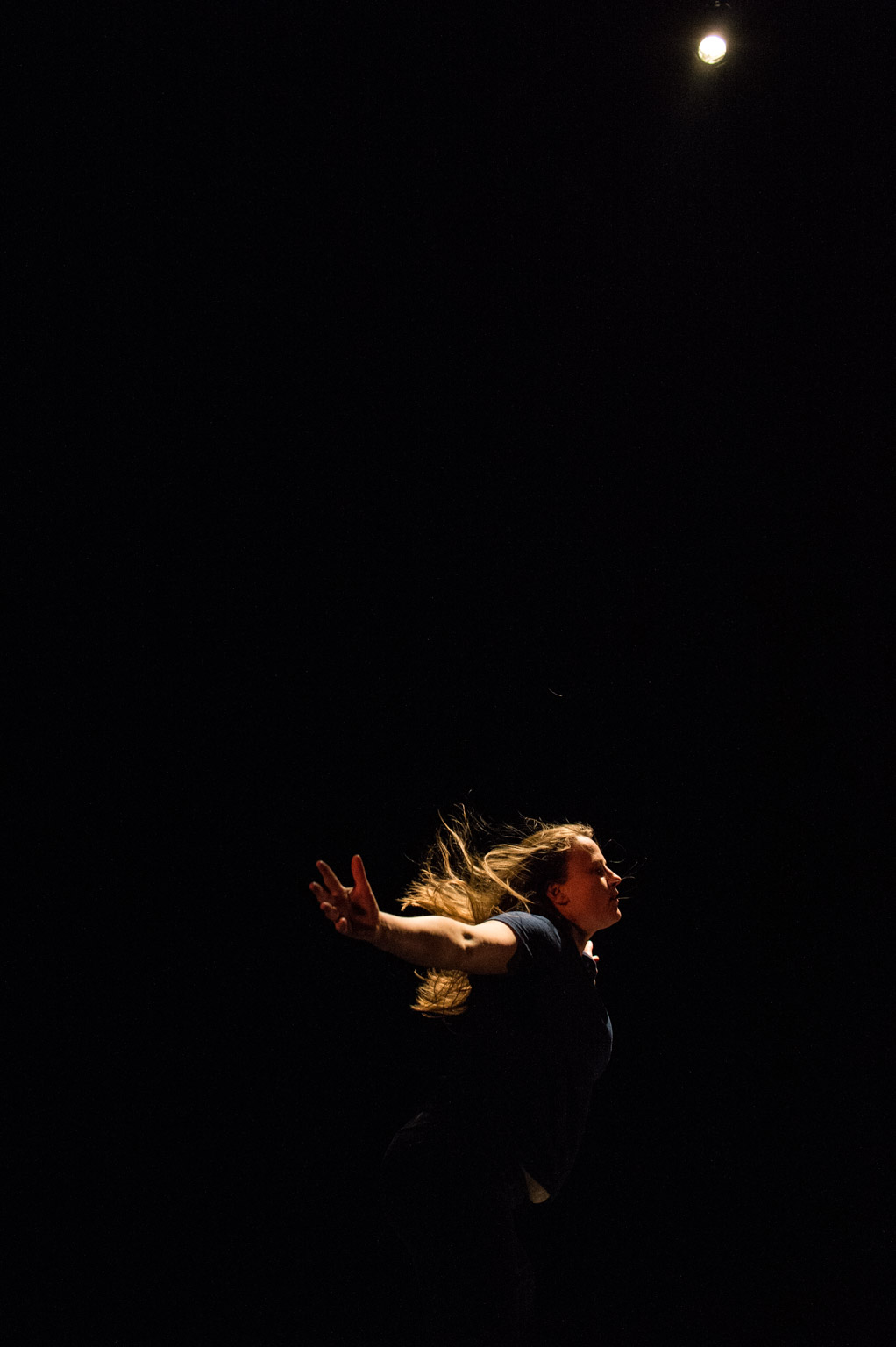

Soon it is time for Withhart’s Solar Probe piece, which she named solar. The stage technicians have dimmed the parchment-colored paper lanterns overhead. Glow tape on the black, floor-level stage provides the only guide for the dancers to take their positions. I can hear their footfalls in the darkness, the artists’ minds no doubt as focused as Young’s before that shuttle flight.

From a Collective performance

Suddenly, a harsh white light blazes stage left, illuminating five female dancers. The pounding beat of Hauschka’s “Elizabeth Bay” echoes through the theater. The dancers perform a series of lifts, launching their partners toward the sun, their hands blocking the light like a sunshield.

As the music builds, the performers advance to the light — reaching deeper into the sun’s cauldron — their moves becoming sharper, stronger, and more vigorous. Their spacecraft has reached the sun’s atmosphere. The temperature spikes to 2000° C, hotter than molten lava. The Sun looks 23 times wider than it does over Baltimore. Sensors, thrusters, and software are working 50 times a second to keep the sunshield pointed at our star. Otherwise, the spacecraft is cooked.

The music is now a higher pitch and unstable, an aural reminder of the solar wind’s electrons, protons, and helium ions buffeting the spacecraft. The dancers must be exhausted and exhilarated at the end of their journey, like the engineers and scientists at the end of a space mission. After practicing and performing, developing and testing, both teams reach a place no one has been before.

It’s here. This is it. This is the time.

The lights go out.

An artist’s rendition of the probe reaching the sun

Sunset

The Collective’s company members return to the stage to receive the audience’s applause. After, their mission over, the dancers share tired hugs with family and friends.

As I leave the theater, the moon has replaced the sun in the sky. The light from the marquee reflects off the Patterson’s red bricks, the theater wall blending into the line of rowhouses on East Avenue. solar is replaying in my mind, serving as an inspiration as Nate and I help build that spacecraft that will one day touch the sun.

Painting reproduced courtesy of Henry Casselli. Artist’s depiction of Solar Probe Plus observing the sun courtesy JHU/APL. Patterson sign by David Robert Crews. The Collective photo by Matt Roth.

Chris Krupiarz works as a spacecraft flight software engineer for the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory. Originally from Michigan, he now lives in Ellicott City, Maryland, with his wife and two kids. In his spare time he enjoys reading and writing, walking in the woods with the family beagles, and creating fictional sporting events with his sons.