I am at work, wearing nothing but a flimsy hospital gown, and there is a student walking toward me. He is shaking a little and sweating a lot, and his face has turned a shade of green. I am sitting on an exam table with the back raised to 90 degrees, with my feet in footrests and a drape over my lap.

“Okay, pause,” I tell the student. He freezes like a deer in headlights. I am trying not to laugh. “You are fine. Take a moment. Close your eyes. Take a deep breath.” He does as I instruct, still very tense. “Keep breathing. Listen to me: I am not going to let you hurt me. I am very good at this. You are going to do great.”

When I think he’s less likely to pass out I let him open his eyes, and give him a big thumbs-up and a smile. He and I both laugh, and so do the four other students standing around behind him, watching anxiously, while obviously thanking their lucky stars they didn’t have to go first.

Looking much more relaxed and no longer green, the student comes to stand in front of me, and we begin. First, I tell him how to position a patient on the table, explaining he should place his hand on the edge, so that she won’t fall off when she scoots down. I tell him he needs to place his hands outside her knees, palms facing outward and about shoulder-width apart, and ask her to touch her knees to the backs of his hands.

Then he sits down, so obviously not looking at my groin that I worry he’ll strain something. “Okay,” I tell him, “now you’re going to place the back of your hand on my inner thigh, so I’m expecting the contact, then you’re going to fold your hand in and use two fingers to separate my labia minora, so you can see the opening of my vagina.”

Ask first

I work as a gynecological teaching associate, or GTA. My colleagues and I take our clothes off and climb onto an exam table, and teach medical, nursing, physician’s assistant, and midwifery students how to do breast and pelvic exams. We are paid to use our bodies to teach doctors of both genders how to care for and educate women. It wasn’t always this way.

One day in 1968, a nurse at the University of Iowa Medical School took a break from her usual work to head over to the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology.1 Maybe she told her colleagues she wasn’t feeling well; she certainly wouldn’t have told them where she was really going. We don’t know much about her, which is how she wanted it, but we do know enough to surmise what she did next.

She went to the assigned room and undressed, before getting up on the exam table and arranging a drape so her face and upper body were hidden from the rest of the room. Robert Kretzschmar, the M.D. who had hired her, entered with several medical students and proceeded to demonstrate a full pelvic exam. Each of the students then attempted to duplicate his actions. None of the students saw her face, and she didn’t speak. This was the first documented pelvic exam of its kind, and though the nurse was willing to try something new, she was not willing to stake her reputation on it. The students never learned who she was.

Despite her anonymity, then and now, this nurse and doctor led the start of a radical and feminist shift in medical education. It was the first time students learned how to perform a pelvic exam on a woman they knew had given her full consent.

Practice makes perfect

Each GTA session is just me and three to six students in a room, and I teach them everything about how to perform an empowering gynecological exam: how to do the techniques correctly and without hurting the patient, what to look for while examining her, how to interact with her with respect, what things to educate her on and how to explain them, and how to get her involved in her own health care by giving her a hand-mirror so she can observe what they’re doing.

The latter two are, in many ways, the most radical parts of the GTA system; they assume that a patient has a right to know what is happening, and that she has knowledge and authority over her body that the doctor doesn’t.

What makes the GTA model of teaching so unique, and so effective, is that the GTAs are simultaneously the patients on whom the students get to practice, and the instructors teaching them what to do. Some programs use one GTA working alone, while some have two GTAs team-teach by role-playing a standard exam and taking turns instructing. What both models have in common, however, is that throughout the entire session there are no other authority figures in the room, such as professors or fully certified doctors — just GTAs and students.

The work is definitely unusual, and requires a particular type of person. But the pay is phenomenal. The work aligns with university semesters: there’s almost no work in January, but there can be multiple sessions a day in October and November. Different programs operate slightly differently, but generally sessions have three to five students, last between one hour and two and a half hours, and pay $150 to $250.

It goes a long way to taking the sting out of having a student faint when you unexpectedly get your period on the table, or of laughing so hard at a student’s joke that the speculum shoots out and smacks him in the face, breaking his glasses. Neither of those things is as uncommon as you might think — or as I might hope.

I know my body extremely well at this point, and I am an expert with the tools; I can teach a student how to insert a speculum correctly while making sure he or she doesn’t hurt me. I have a hand-mirror so I can see what she’s doing, and I’m very comfortable reaching down to adjust his hands or quickly stop him.

If a woman who isn’t familiar with the exam is lying on a table, half naked, while a medical student tries to insert a speculum and a doctor instructs him, she is unlikely to feel qualified to provide unsolicited feedback, and the student will not learn to be sensitive to his patient’s needs.

It can also be hard to know for sure that a student is performing the technique correctly if the teacher is just watching the exam: the instructor can tell the student how to feel the ovaries without being sure the student has actually found them and isn’t feeling something else entirely. I know what it feels like when someone has found my ovaries or cervix, and I can tell a struggling student exactly what adjustments she needs to make.

Gynecology’s troubling origins

My experience isn’t anything like that of the nurse 45 years ago, but I am her direct descendent. She is our mitochondrial Eve: the first GTA. But whereas for me and my colleagues our work and its heritage are marks of pride, GTA Eve apparently felt concerned about her reputation, and hid her pioneering work from her family and colleagues. She didn’t want them to think she was “that sort of woman.” She had reason to fear: gynecological examinations come with an ugly history.

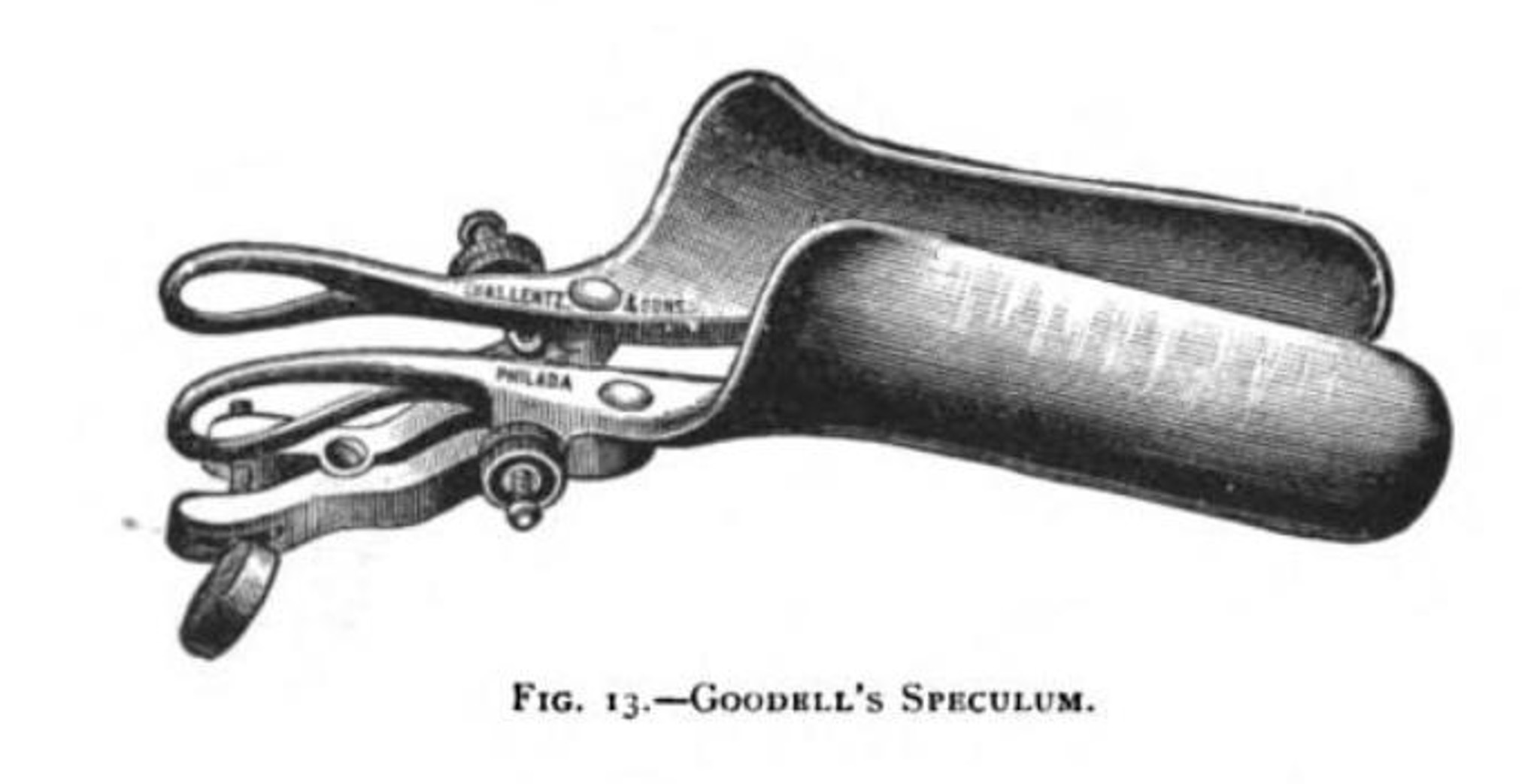

Gynecology as we think of it today began to emerge in the mid-1800s, when J. Marion Sims, M.D., often referred to as the father of modern gynecology, began experimenting with treatments. Sims invented the speculum, the tool that today is virtually the symbol of gynecology, and pioneered new surgical methods for serious problems. He even managed to cure vaginal fistulas — small, painful tears in the walls of the vagina that can lead to bleeding, infection, and urinary incontinence. (This treatable problem remains a source of social and physical trauma for an enormous number of women in developing nations today.)

But he achieved this by experimenting on non-consenting slave women, without using anesthesia, even though it had recently become available to surgeons. He performed over 30 operations on one of his subjects, a woman named Anarcha.

Though the results of his experiments were ultimately used to improve the quality of life for white women, they began as a way to protect the earnings of slave owners: female slaves with painful gynecological problems couldn’t work as hard, and their value was drastically reduced if they couldn’t give birth to children, who would also be enslaved.

Sims (and many others) also frequently sterilized and experimented on women with mental disabilities, again without their consent. These patients had no voices. They couldn’t refuse; they couldn’t criticize or offer unsolicited feedback; they couldn’t make demands. Even after these practices were outlawed, those qualities remained desirable, and doctors found other sources of voiceless women to teach their students on.

A lack of consent

Through the 1970s, the common practice was for four or more medical students to practice vaginal exams on female hospital patients too cowed by the attending physician to say no; to use anesthetized patients who had not been clearly informed, let alone given explicit consent; or to work with plastic models.

While one might think a plastic model would be by far the best option, as it is the only one that did not require a form of sexual assault, the models’ standardized anatomy actually forced an incorrect insertion of the speculum, and it’s impossible to palpate them to locate glands or ovaries. This led to inexpert handling by doctors who had never worked with actual women.

All three methods teach student-doctors that they don’t need to listen to their patients, and though they learn the techniques well enough to diagnose their patients, they don’t learn how to do them without causing discomfort.

Around the time that Kretzschmar and his unnamed nurse assistant had their first examination session, doctors had already become aware that a change was needed, and consent would need to be obtained. A common solution was for hospitals to hire prostitutes, who would seemingly have few objections to either the intrusive physical act or the pay. To keep matters professional, they were told to act like regular patients, and medical students were informed neither of the women’s profession nor that they were compensated.

These women had more of a voice, and could offer feedback, but many lacked the vocabulary, language skills, or even accent that doctors would listen to. Kretzschmar’s solution was to hire educated women who were paid to receive the exam and provide feedback, and to whom authority was given. Over time, he refined his program to add the option for a pair of women with the same training to swap roles between patient and educator.

Defining normal

Women are bombarded with media and social critique of everything about their physical appearance: nothing is ever quite right. Labiaplasty, which is cosmetic surgery for the labia, has become common.2 It is challenging to find clear statistics about its prevalence, as it is controversial enough that doctors tend not to report how often they perform it. It has no purpose except to make the vulva appear more “normal,” which in this case means resembling that of a pre-pubescent girl. Whether it is a result of images from pornography or not, there is a widespread belief that inner labia should be nearly invisible, or at least small and neatly contained by equally small outer labia.

GTAs teach students to end each part of the exam by telling the patient, “everything looks healthy and normal.” It’s a great way to let her move on to the next part of the exam. Even more importantly, it is an amazing use of the authority conveyed by that white coat to help her start thinking of her body as being completely fine as it is.

When students see a GTA being comfortable with her typically unmodified body and talking about all the ways it is healthy and normal, it can be earth-shattering, for both the men and the women. At the beginning of a GTA session, usually all of the students are terrified. Sometimes a student (usually male) is very reluctant — universities that use GTAs make all their medical students attend a session, which includes students on track to be anesthesiologists and researchers, who are right when they say they won’t often use these skills in their careers.

But by the time we’re on to the pelvic exam, the students are enthralled, and the men are as interested as the women. The women are often thoughtful, and say things about how it’s different than what they imagined, and they’re so grateful I’m doing this. They talk about how strange it is that they knew so little. There is often a wealth of emotion behind those statements.

The guys, however, are just totally stoked. They react to the first sight of my cervix like I imagine astronauts do the first time they step out onto the moon. They want to be able to care about and for women without hurting them, but they don’t know how. They are afraid to ask, because nothing in their lives has taught them how to do so without being creepy.

At the start of the session they are nervous or reluctant, but when they realize I am not going to judge them, that I am going to teach them how to talk to me and ask what they want to know, they open up. They exude an uncomplicated sort of excitement that is in no way untoward or sexual. They repeat “wow!” and “amazing!” over and over.

Shaping the story

One of my female students felt my cervix for the first time and her eyes filled with tears. She stayed after the session and told me about how she had been assaulted as a young woman and blamed by her friends for inviting it. She said this was the first time that she didn’t feel like there was something bad about her body. It was so amazing to think about her body working exactly how it was designed to, and realizing that there was nothing inherently wrong with that — quite the opposite, in fact.

No one benefits in a system that turns half its members into objects to be acted upon by the other half. That can be true in male-female relationships, in race and class relations, between doctors and patients, and of students and teachers.

People on the dominant side of a dynamic aren’t doing themselves any favors either, and often they are unintentionally reproducing the patterns they were taught: the doctors who didn’t see their patients as people missed out on all the valuable feedback they could have received to improve their skills.

GTAs who interact one on one with medical students shape the stories about the female body that the students will carry with them as doctors and pass on to their own patients. Maybe it’s a small thing, but maybe not. I just know that I want to live in a world where a teenage girl leaves the clinic after her first, nerve-wracking pelvic exam, thinking, “Yeah, my cervix really is cool.”

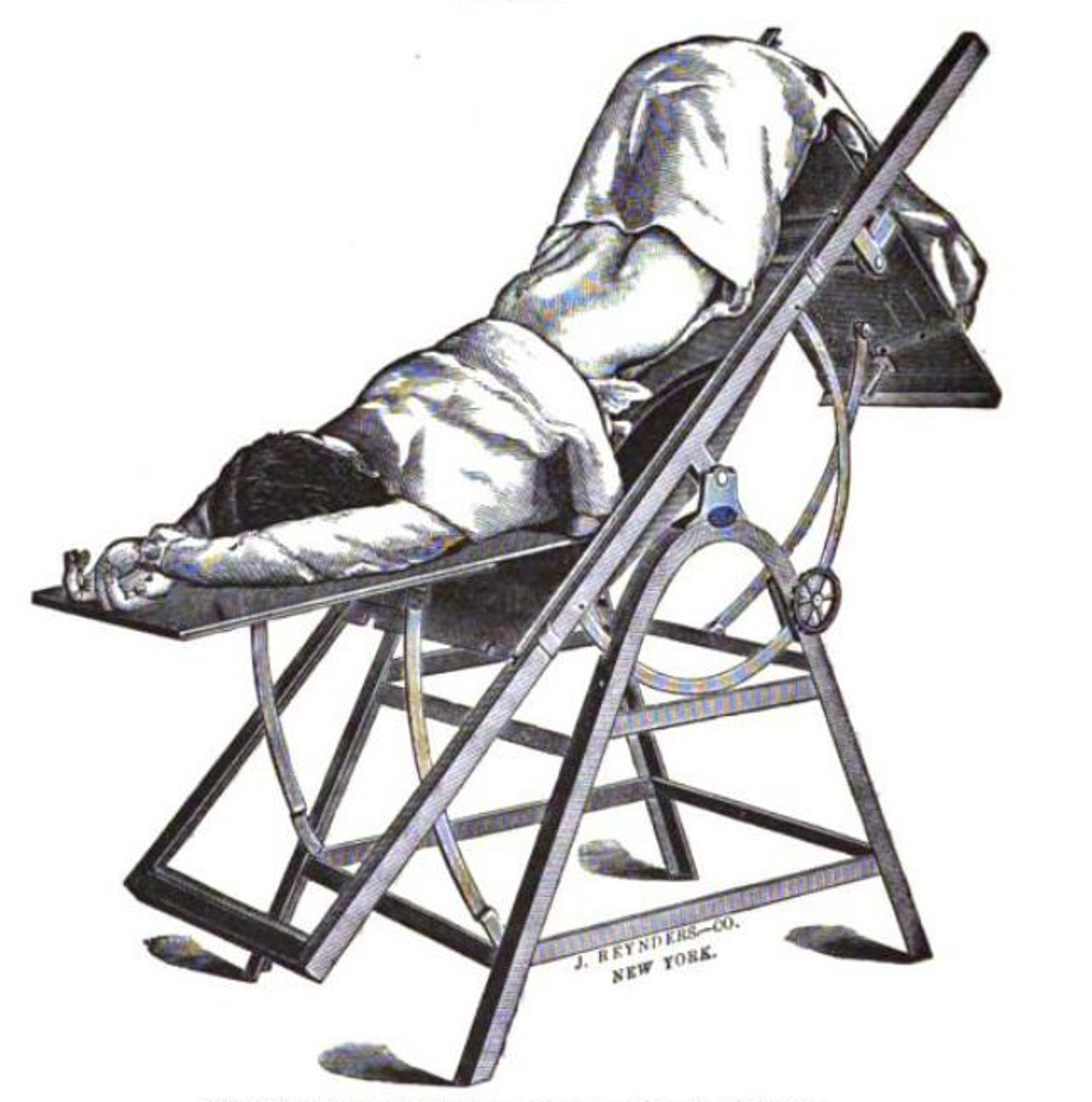

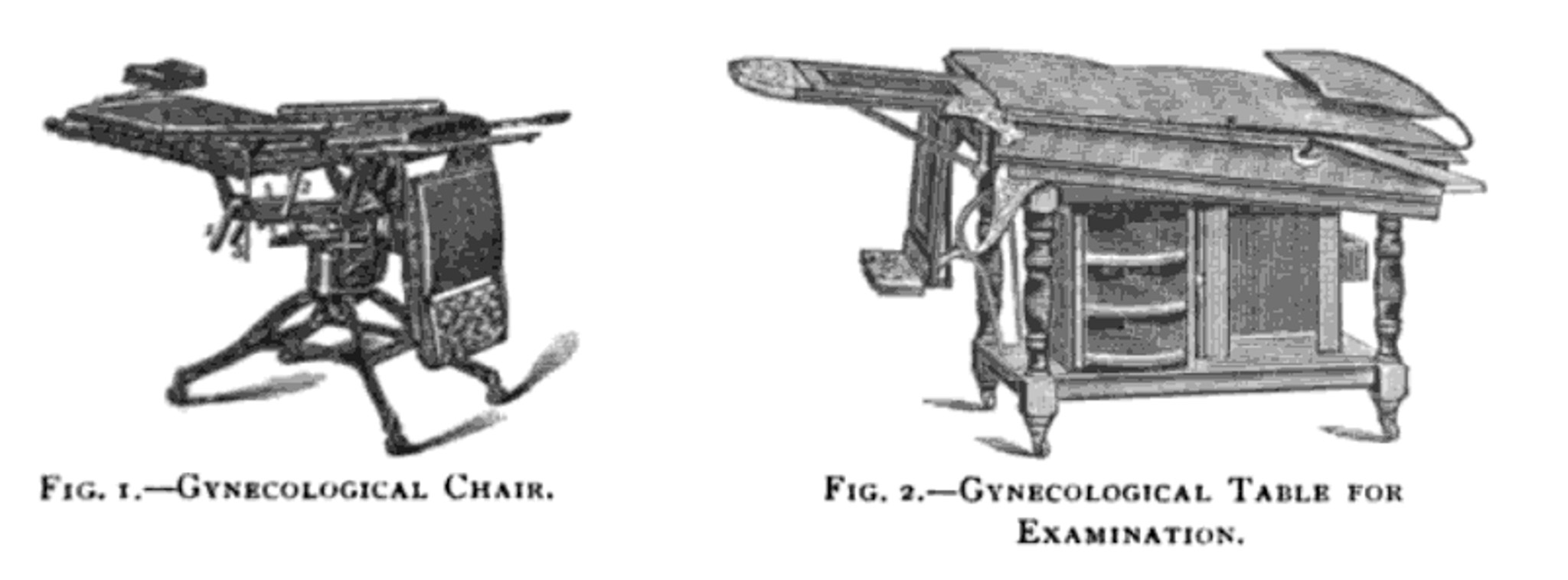

Illustrations from Clinical gynecology, medical and surgical for students and practitioners by eminent American teachers (1897), Manual of Gynecology (1897), and Lessons in gynecology (1891).

-

In Public Privates: Performing Gynecology from Both Ends of the Speculum (1997), Terri Kapsalis recounts the history of this examination on pages 68 and 69, which you can preview at Google Books. ↩

-

The British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology published a study in 2009 that, according to the Guardian, “revealed that there had been an almost 70% increase in the number of women having labiaplasty on the NHS on the previous year.” ↩

Alexandra Duncan is a gynecological teaching associate, a full-spectrum doula, and a beginning freelance writer. She recently graduated from NYU's Gallatin School and is attempting to figure out how to be a grownup.