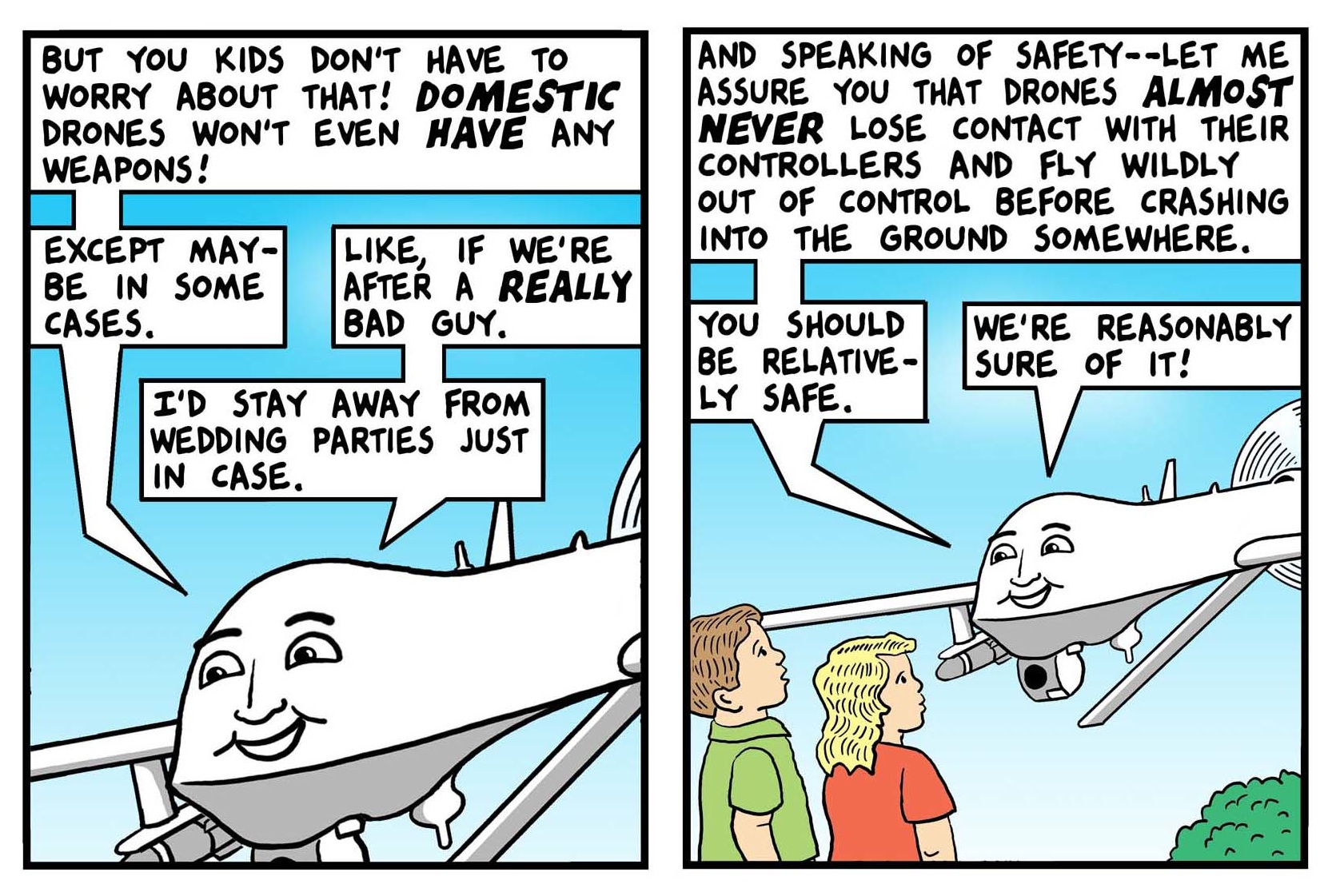

“Droney,” part 2 of 3, from This Modern World by Tom Tomorrow.

Return to Part 1.

Backyard panopticon

“That’s a goddamn expensive revenge,” Skeeler said in the limo, after I worried about a scenario in which some guy uses his iPhone to fly a personal drone to an out-of-sight location and hurt someone who’s upset him. I replied that it’s really not that expensive: A low-end drone today is probably cheaper than a hit man. That price will plummet in the not-too-distant future.

Skeeler still shrugged off the risk, suggesting instead that there’s a far worse scenario. For him, it’s a rerun of 9/11, which occurred when he was 10. Replace the first plane to hit the World Trade Center with a terrorist bomb strapped to a Parrot AR.Drone, he said. Then imagine a squadron of New York City Police Department drones designed to stop the bomb-laden Parrot. “Who do you think’s gonna win?” he asked.

Skeeler was not unique at the competition in having a sanguine attitude toward potential bad outcomes of domestic drone technology. Another young drone-builder, David Cape, a 21-year-old mechanical engineer from the University of Southern California, told me to disregard the many student drones that were crashing — and, in one case, burning — around us as they tried to finish the contest mission. Cape said few airplanes have such mishaps today, “but in the early days they were crashing and burning all the time.”

Fair enough. But what about some stable, neither crashed nor burned drone that ends up hovering above me, recording everything I do with its high-powered camera?

“What would it be taking a video of,” Cape asked me. “Your life?”

I was thinking, Yeah.

His point was, Who cares?

“Sure, it might be invading your privacy,” Cape continued. “But if someone really wants to see me walking to class, that’s cool.”

It appeared it was all just flying Facebook to him, so I tried a slightly more specific scenario. I asked: What if the drone is watching me in my own backyard?

Cape’s teammate, Reese Mozer, 20, shot back, “What are you doing in your backyard that someone would want to spy on you about?”

“Our reasonable expectations of privacy are shifting,” Anderson of DIY Drones explained when I related this exchange to him. “We can’t even, as a country — much less as a community — we can’t agree on what we collectively want. But we can evolve the law.”

However, Anderson’s own community of Berkeley, California, found out last year that the current law does not allow local jurisdictions an easy way to ban drones. The city’s Peace and Justice Commission, an official advisory board to the Berkeley City Council, attempted it. The commission recommended a flat-out prohibition on drones in that city’s airspace, which the city council rejected in favor of more study. But Anderson points out that Berkeley doesn’t legally control its own airspace, an issue also raised by a sensible city council member.

The fact that the proposal was bounced was fine with Anderson, who sells plenty of personal drones to people in cities like Berkeley. Still, it hasn’t stopped many other city councils and some 30 state legislatures from wading into their own attempts to put drones on leashes.

Batman, yes; speeding, no

Even as the domestic drone boom and backlash have been building, few pollsters have asked Americans to think about the implications of robots flying above their heads. (Though Senator Paul’s speech may change that.) Plenty of polls have asked about overseas drone strikes; a February 2013 NBC News/Wall Street Journal survey found that 64% of Americans support using drones to target members of Al Qaeda and other terrorists abroad. Also in February, CBS News found that even if the overseas target is a suspected terrorist with American citizenship, 49% of Americans still approve of killing that person using a drone strike — as the Obama administration has done in three controversial instances.

But Patrick Murray, director of the Monmouth University Polling Institute in New Jersey, believes he is the only pollster to have asked Americans specifically about the impact of drones in their own skies, and my research bears him out. His June 2012 poll of 1,700 adults found strong majorities in favor of using domestic drones to help government agencies with search-and-rescue emergencies and to aid authorities trying to stop illegal immigration.

The poll also found, somewhat confusingly, that while 67% of Americans support using drones to chase runaway criminals, 64% of Americans would be concerned about their own privacy if police departments started using drones equipped with high-tech cameras. That same sense of wanting drones to chase bad guys but not bother good guys (i.e., poll respondents) showed up in another of Murray’s poll questions: “Do you support or oppose the use of drones to issue speeding tickets?” Drone-issued speeding tickets were opposed by 67% of Americans — the same percentage that want drones to track down lawbreakers.

“In many ways we were catching our respondents cold,” Murray said of his domestic drone polling. “It was something they hadn’t thought about before.”

Also interesting was the response from the 18-to-29 cohort. Although every age group in Murray’s poll showed strong majorities opposed to using drones to issue speeding tickets, that youngest demographic had the most people in favor of this idea — and nearly the fewest opposing it (ignoring a small margin of error). When I heard this, I thought of Mozer, the USC student who’d asked me at the competition, “What are you doing in your backyard that someone would want to spy on you about?”

It’s a view that transforms worry about drones into something close to an admission of guilt. If this becomes a common view among young Americans, who are already more used to sharing the intimate details of their lives online, then our domestic drone debate is going to resolve in ways far different than either the ACLU or Charles Krauthammer would prefer.

Everyone’s a pilot now

There may be an additional element making some younger Americans less hostile toward drones. In a Harvard Crimson roundtable discussion published in February, freshman David Freed noted, “Although the drone campaign is a burdensome evil abroad, it is a preferable domestic political strategy because it keeps young Americans in school instead of on the battlefield.”

Even with an all-volunteer army, students may be particularly attuned to missions that seemingly require fewer soldiers. And, as students likely know, some of the soldiers participating in drone missions trade time in a dangerous war zone for a seat in front of a joystick inside an air-conditioned, satellite-connected trailer somewhere in New Mexico.1

The controversial use of armed drones in warfare has incited many protests, including this one against John Brennan, the architect of the U.S. drone war against Al-Qaeda, in Washington, DC, on February 7, 2013. Photo by Jewel Samad/AFP/Getty Images.

Another tradeoff that doesn’t seem to be inciting outcry among the next generation: the morphing of the term “pilot.” The University of North Dakota, where the drone-building competition took place, used to be hyped by boosters as the Harvard of pilot training. While I was on campus for the competition, I learned that the university is now trying to become something else: the Harvard of unmanned aerial vehicle “pilot” training.

One day, after walking over a university skybridge paid for by a potato farming magnate, I stepped into a school store and ran into 22-year-old Alec Lindsey, who was buying some University of North Dakota gear to celebrate his pilot training graduation. He told the classic tale of growing up believing he was born to fly, of wanting to be an astronaut and then settling on the more achievable aim of becoming a pilot. When he considers the idea that one day soon he’ll be replaced by a flying robot, he’s already prepared. “That’s actually what my major is,” he said.

A quadrotor world

The drone-building competition in itself was rather boring. Its implications were enormous, but its theatrics involved a lot of standing around waiting for coders to tweak programs and for batteries to finish recharging.

One of the most exciting moments occurred after lunch, when a drone developed by a team from Bangalore went out of control and drifted sideways toward the timekeeper’s table. The woman keeping time had to shield herself with the lid of a plastic bin to keep the drone at bay. Papers went flying from the wind the drone’s rotors were kicking up, a contest organizer belatedly hit the drone’s kill switch — required for the competition — and the Bangalore team, like the OSU team before it, was forced to withdraw.

Later on, as the competition drew to a close, someone finally asked that music be played over the loudspeakers. It had otherwise been an entire day of brief announcements and the buzzing of student quadrotors. In a stroke of unintentional genius, a former DARPA employee who was manning the mic put on David Bowie’s Space Oddity, the first chords of which brought on the feeling of mystery and foreboding that had been missing from this gathering: “Ground control to Major Tom…”

Here was a very different story about airborne technology than was being told at this competition, which had as its logo the world on a quadrotor. It was a story in touch with hubris — a story of a man sitting in a tin can far above the moon, calling, “Planet Earth is blue, and there’s nothing I can do…” Angry guitar strokes, and then, from the engineers below:

Ground control to Major Tom, your circuit’s dead, there’s something wrong. Can you hear me, Major Tom? Can you hear me, Major Tom?

The Predator

To clear my head after the contest ended, I went for a drive. There are no suburbs of Grand Forks, so it was just boom: corn fields, sky, not a hill in sight. Dust rising behind a thresher in a field of tow-headed wheat. Grain silos. Then an actual military base: the Grand Forks Air Force Base, with its grass-roofed hangars and its outdoor museum of old planes and intercontinental ballistic missile equipment, a display that doubled as an accidental monument to the Cold War theory of mutually assured destruction.

I eased my compact rental car up to the enormous nose of a B-52 and got out. I recalled how at the competition Kahn, the conference organizer who works at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory, had said, admiring the compactness and sophistication of the student drones, “What’s crammed into these little vehicles was not even conceivable cramming into a B-52.” I listened to the crickets, watched some dandelion thistles blow by. A large dragonfly buzzed past, and I recalled reading that military contractors can make drones that small now.

Back in my car, I drove toward the end of the runway where the border patrol’s Predators take off and land. As it happened, one was circling low. I pulled over, threw open my car door to jump out, and as I was doing so was halted by beeping that told me I was about to lock my keys inside. I thanked my robot assistant, grabbed the keys, and stepped out onto the shoulder.

The Predator was above me in a bright North Dakota sky, marked by a windowless frontal bulge where the cockpit should be and a set of distinctive tailfins pointing both upward and downward. It made a turn with a crispness that was unmistakably mechanical, sharper and quicker than any human could achieve given the vagaries of flesh and muscle and tendon attached to bone attached to brain. It was a turn not so much elegant as brutally efficient. I listened to the Predator’s dull and distant whir. Then it banked over a plowed-under field, lined up on the runway, and landed silently in the distance.

Continue to Part 3.

Cartoon by Tom Tomorrow.

-

Whether fighting like this is courageous is another and hugely controversial question. Operating a drone from air-conditioned confines may come with its own unique forms of PTSD, but there is currently intense debate over whether drone operators should be eligible for a special warfighting medal that, at present, outranks the Bronze Star and Purple Heart. ↩

Eli Sanders is an associate editor at The Stranger and the winner of the 2012 Pulitzer Prize for feature writing.