The photographer and I ride up in a large and noisy elevator. Our chaperone points to the photographer’s camera. “You should use a Polaroid camera in this building,” she says. “This is still an old-fashioned digital one,” I reply. She smiles and repeats my words softly and slowly. “An ‘old-fashioned’ digital camera. That’s funny.”

In Enschede, a town on Holland’s eastern border with Germany, factories churned out textiles and other products from the early 19th century until the 1970s, when the last shut down due to competition from Asia. The Polaroid film factory was a late arrival, built in 1965 and shuttered by the firm in 2008. But a brightly colored phoenix rose almost immediately from the ashes, and the plant brims with energy today.

As digital photography and digital photo printing became increasingly affordable, demand for Polaroid film plummeted. The firm filed for bankruptcy in 2001, and the new entity that bought its assets decided in 2004 that instant film’s future was dim. It stockpiled what it thought was enough chemicals to meet demand for new film for a decade, and dismantled its ability to make more. Film sold faster than expected, depleting reserves. Meanwhile, the new Polaroid began closing its factories as it tried to shift to putting its name on and making digital products. It stopped making instant cameras first, then film. The new Polaroid filed for bankruptcy in 2008.

That would have seemed to be the end for Polaroid film, even as the company assets were sold again and the name slapped on unrelated digital cameras and other products. The knowledge of thousands of workers across many decades was scattered. But the Enschede plant’s closure contained the seeds of the return of an instant film, lacking just the Polaroid name.1

But that’s Impossible

Florian Kaps, an Austrian entrepreneur, met André Bosman at the closing party for the Enschede factory in 2008. Bosman was the factory manager whose job it was to shut down the complex, while Kaps ran a Web site selling Polaroid products. Kaps and Bosman both loved Polaroid’s instant film and decided to save this last factory and find a way to continue production. They both felt there was still a strong demand for this type of photographic magic.

Kaps contacted Polaroid with a plea to hand over its production secrets. “We have shut down,” the regretful Polaroid manager replied. “What you want is impossible.” That didn’t deter them; rather, it was a call to action. Kaps and Bosman started the Impossible Project. They leased the Enschede building and bought many of the machines that made Polaroid film, but they couldn’t acquire the formulas, processes, or raw chemicals. Instead, the company had to re-invent Polaroid’s magic with enormously fewer resources.

One can find many accounts of this period of the Impossible Project’s life (both before and during the launch of its film products in 2010), such as Wired UK’s lengthy feature from 2009. But outside of photo magazines and sites, precious little has been written since, even as Impossible has expanded production and continued to raise significant capital.

The firm says it shipped 500,000 packs of film in 2010, 750,000 in 2011, and nearly a million in 2012. Sales continue to climb. Capitalized initially with €1.2 million (about $1.6 million) from friends, family, and angel investors who went on to chip in an additional €3.5 million ($4.5 million) through 2011, the firm says it raised unspecified “significant funding” in 2012 for substantial expansion of its work. Impossible hosts project spaces in New York, Paris, and Japan. (Japan’s Fujifilm continues to make its own instant products.) Its headquarters are in Vienna, but its main research and development efforts remain located in the old factory in Enschede.

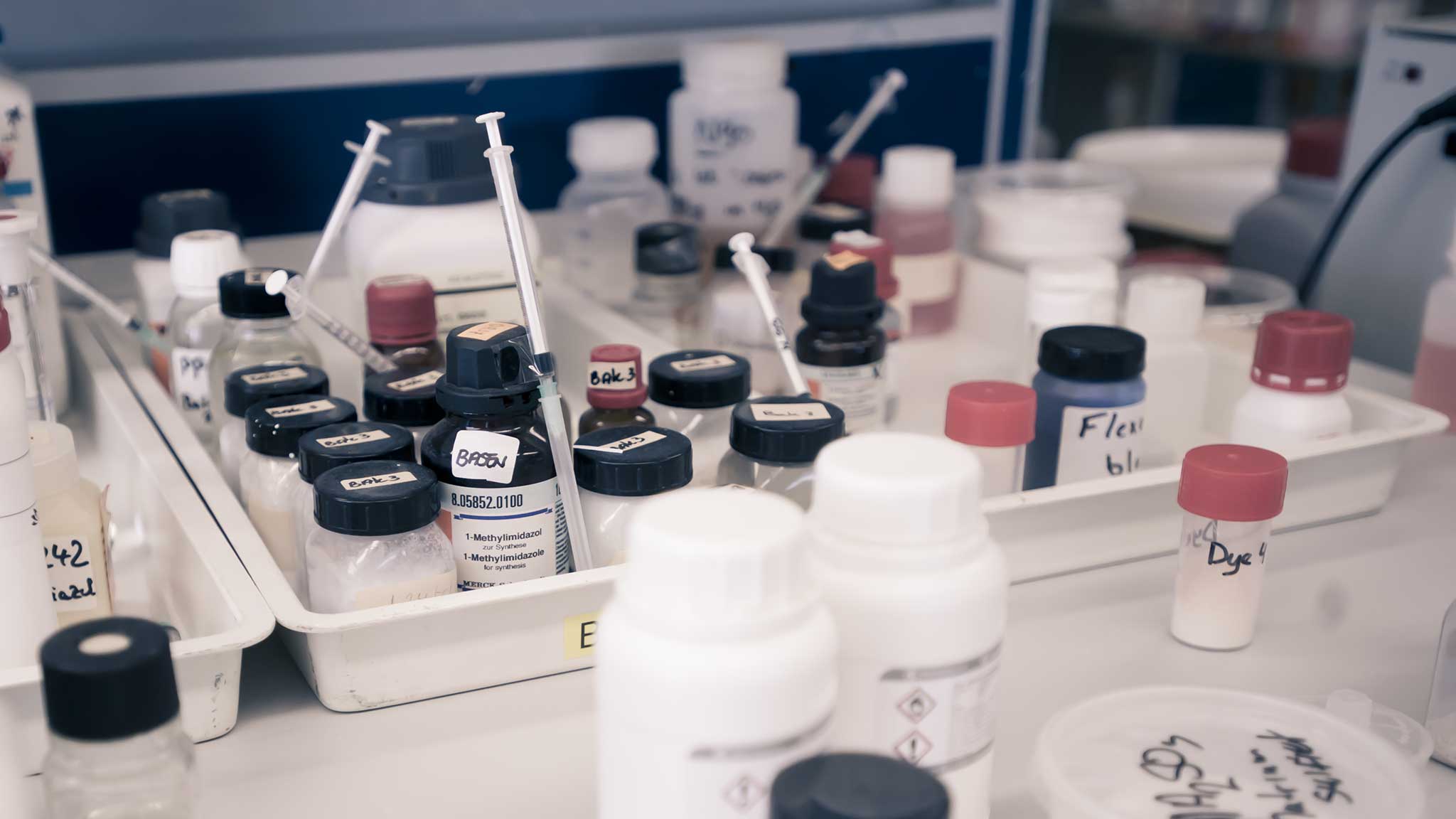

On assignment for The Magazine, I visited the plant with a photographer in February 2013 to see how the Impossible Project had become entirely possible. We met Martin Steinmeijer, the project’s chief chemist and a precise, enthusiastic, and hard-working man, like so many in this part of the Netherlands.

Steinmeijer takes us to a large room where dozens of developed instant photos lie on a table. Some are overexposed; some too dark. Steinmeijer explains, “These photos have been shot in a cold room in our lab on our new PX 100 black-and-white film. You can see that they have not developed the way they should in temperatures far below zero. Not a major problem in everyday use, but we have to fix it.”

Steinmeijer clearly is a perfectionist. “Polaroid’s production used to be fragmented,” he tells me. “In this factory we mainly produced the chemical paste needed for the development of the film, and we manufactured the film packs. The negatives, the sheet material, and the pigments all came to us from the United States. We had no knowledge of the techniques whatsoever.”

But in 2010, the project started developing instant films that can be used in almost every old Polaroid camera, like the Polaroid 600 and SX-70. The new media include both monochrome “silver” and full-color film, which rely on completely different techniques. Impossible says they even improved the old Polaroid qualities. The films have “never seen before color saturation, a completely new level of detail and sharpness, and overall stunning image quality,” according to its press releases — and confirmed by reviews and my eyes.

I appreciate the fine, warm colors in these images as opposed to the hard, sharp prints that often come from a modern digital instant-print camera. Kirstin McKee, a London photographer, likes the film for its variation. McKee was recently featured on the Impossible Project’s blog for photos she took on a trip to Crete. She says via email that she has found instant-film pictures appealing for a few years, and started “trawling eBay” to acquire Polaroid cameras to try out with the project’s film.

McKee says Impossible’s film “is a pleasing contrast from the reliable repeatability of digital imaging. Polaroids are, in other words, more like memories. They are unreliable, rose-tinted, and capricious, and their characteristic format is somehow inherently nostalgic.”

Speeding up

The firm sells several varieties of film for about $3 an exposure, mostly in packs of eight. The price and variability of results mean the film currently appeals mainly to photographic artists rather than general consumers. A Flickr group for instant-film shooters gives a good sense of how Impossible’s film (and the precious remaining Polaroid stock) is being used. But there are other drawbacks that Impossible must overcome before it can reach even a fraction of the mass audience that Polaroid once captured.

“One of the most appealing aspects of old-style Polaroid photography is seeing your photo develop in a few minutes after shooting. This is a unique experience totally absent in modern digital cameras,” Steinmeijer says. “But with our films it takes much too long for the picture to appear.” He sounds worried.

Impossible’s first films have two problems. After shooting, the negative behind the photo sheet remains very sensitive to light, and it has to be shaded the instant it comes out of the camera. The first half-second is critical, but an exposure must be kept out of the light for up to four minutes to be safe. On top of that, full development takes 10 to 20 minutes.

A new color-protection film, which has greater saturation as well, solves the problem of extreme light sensitivity, but still takes a long time to produce an image. (The monochrome film retains both issues, and the older color film is still sold.) The new film, released in late 2012, squeezes a layer of opacifier over the sheet as it comes out of the camera. This layer, only about 0.1-millimeter thick, consists of protective titanium dioxide and indicator pigments, and protects against all but full sunlight.

The pigments decolorize (change from opaque to clear) in about half an hour after the negative has been developed and is no longer photosensitive. But the developing process requires just five minutes in the new film. Impossible is trying to narrow that gap. “It is a huge challenge to bring that back to exactly the time needed,” Steinmeijer explains. “When your picture develops, you should be able to see the chemistry taking place in the palm of your hand. We are not that far yet. We are working very hard on this problem.”

Of course, that may be part of the charm of Impossible’s film at this stage of the market’s development. Photographer McKee notes that “instant” pictures have a process all their own: “It does not appear, immediately and flawlessly, on the camera’s screen, but takes its own sweet time to develop, often in unpredictable ways.”

Shake it like a smartphone

Today, Impossible is the only company producing instant film for original Polaroid cameras. But the project is not only about reviving Polaroid instant photography. Last year it developed its first new hardware concepts. In an office at the Enschede factory, the firm showed me a prototype of a fascinating invention called the Impossible Instant Lab, which captures the image on an iPhone screen onto instant film.

Just launch the Impossible-designed app and select a picture. Place the iPhone in a cradle on top of an expandable hood connected to the newly designed film-processing unit, which contains mechanical gears that process and eject the photo after shooting. Then open the shutter. The app flashes the picture on the iPhone screen just long enough to expose the film. The sheet rolls out of the processing unit, and you can see an “analog” iPhone image develop in the palm of your hand. Just like old times, but with a digital twist.

The Impossible Project used crowdfunding to raise the funds for Instant Lab. It had a target of $250,000 and raised nearly $560,000 on Kickstarter. The funds will allow it to go from a working prototype into mass production, with an expected price of $300. Although Instant Lab was promised to be available to Kickstarter backers in February, the usual delays between early prototypes and the production line have pushed delivery back to no earlier than April.

But the Instant Lab isn’t a single project. The film-processing unit that’s part of it will form the basis of new instant-film cameras already in the design phase. “If you place a lens on the front of the processing unit together with a mirror, then you have a Polaroid camera,” one of the researchers explains. He takes a Polaroid camera from the 1970s out of a glass case. The two designs are basically the same.

It is never easy to re-invent a 20th-century success story from scratch. And in a time when everything needs to be small, fast, and portable, will a mass market for instant-film photography once again develop? Steinmeijer and the rest of the dedicated team in Enschede believe it will.

“Surprisingly, it turns out that our consumers are also youngsters, who have never been familiar with Polaroid anyway. Apart from artists, we also want to make our instant film practical for people who just want to take a quick picture. Instant film is such a wonderful, quick, and easy-to-use product. That is the reason we think we can re-conquer the large group of customers Polaroid once had,” he says.

Photographer McKee has a simpler answer: “A Polaroid links me physically to the past in a way a digital image never could.”

Photos by Laura Muns.

-

Photographer Robert Burley spent several years documenting the worldwide shutdown of analog film operations by Kodak, Polaroid, and others in his book “The Disappearance of Darkness,” which also has a chapter about the Impossible Project. ↩

Maarten Muns is a science and technology reporter based in Haarlem, the Netherlands.