The remnants of the Hamilton district in Two Rivers, Wisconsin — the former headquarters of the country’s largest producer of wood type in a town that once hummed with manufacturing — now largely sits quiet. The industrial building housed two last bits that came out of over 100 years of wood manufacture: a laboratory furniture operation, and the Hamilton Wood Type Museum. Save some old business cards scattered on the ground, the factory is empty.

Thermo Fisher Scientific, the descendant owner of Hamilton Wood Type Manufacturing and its buildings in Two Rivers, announced abruptly in 2012 that it would shut down its furniture division in Two Rivers. The museum was forced to move, and found a space a few blocks away. Now relocated and only recently chugging back to life, its unofficial motto is unchanged: “Preservation through use.” The museum houses one of the few remaining shops in the world that can produce wood type, a mainstay for a century in the production of many kinds of printed work.

Like vinyl records, the sales of which have climbed back into the millions a year, wood type appears to be getting its groove back. A branding and exposure makeover for the museum, combined with the rapid rise of maker and crafts movements, have helped wood type carve out a new space.

Wood type has kept its appeal even as the born-digital generation starts to take charge of the world, maybe because members of that demographic have become aware of what they are missing. Current museum director Jim Moran says he can’t teach enough traditional letterpress classes to satisfy demand. He believes if he had more time to carve new wood type, he would be able to sell every last piece.

Type-cast

From Gutenberg’s day to the early 1800s, movable type was cast in metal; wood blocks were used primarily for illustrations. Then in 1827, Darius Wells disrupted the industry by coming up with a way to mass-produce wood type for large letter sizes that had begun to be desirable for advertising and newspaper headlines. This had numerous advantages over metal type, which was expensive to cast at such sizes, remarkably heavy, and susceptible to warping before it was cool. (For more on metal type in this issue, see the editor’s note and Nancy Gohring’s “Inkheart.”)

Wood, on the other hand, was relatively cheap, light, resilient, and could be carved with smooth surfaces. Wells released the first known wood type catalog just a year later, a move that led wood type to share the market with metal for almost 150 years.

In Two Rivers in 1879, James Edward Hamilton began working at a chair and table-making factory as a lathe operator. Hamilton’s friend Lyman Nash, then editor of the Two Rivers Chronicle, felt Hamilton’s skills could be put to better use — namely, to carve letters for a poster he was printing on a tight deadline. Nash knew he could never get type delivered fast enough from the East Coast, where all other type was made, so he asked Hamilton to carve something — anything — he could use to get the poster done on time.

“Hamilton didn’t know anything about type,” Moran says. “He didn’t see the future of it or anything like that. He was simply helping out a friend.”

With no background in type carving, Hamilton came up with his own style: cutting the characters out and gluing them to blocks of wood. The process was cheap but effective — so much so that Hamilton found himself making more and more type for Nash’s posters. Hamilton’s hand-carved type evolved to the point where he thought he could turn it into a business, and in 1880, he did.

“Hamilton’s business grew at such a rate that, as competition will do, some people were forced out of the market. Others simply sold to Hamilton because it was the easiest thing to do,” Moran says of Hamilton’s sudden success in the typemaking industry. The company’s rapid growth can be attributed to the fact that every time he acquired a competitor’s fonts and techniques, Hamilton would refine his own carving methods. (Hamilton also made type cabinets to store metal and wooden types, first from wood and later from steel.)

One of his most notable acquisitions was the William H. Page Wood Type Company. “When Hamilton bought out Page, he switched to Page’s way of making type, which was to make it out of a solid block of maple wood,” explains Moran, adding that Wisconsin and much of the Midwest has a vast maple supply. “He kept buying out competitors and refining his techniques, and suddenly he had the entire market.”

Indeed, it only took 11 years for Hamilton to dominate the wood typemaking industry; by the turn of the century, nearly all of Hamilton’s competition had either been absorbed or eliminated. Hamilton had become the king of wood type in the United States without ever intending to do so.

Fossilized remains

Hamilton’s manufacturing company stopped cutting its own type more than a hundred years later, in 1985. Moran calls this “way late,” considering that Apple’s first Macintosh computer was released in 1984. By then, demand for traditional type and typesetting was understandably limited as computers were quickly revolutionizing type and design. Type enthusiasts prepared for the death of wood type and kept trying to buy Two Rivers patterns for private collections.

“Each piece needs a template, and you’d have all these pallets of these gorgeous patterns that were collected over time,” Moran says. “That was all about to be sold, and that’s when the Two Rivers Historical Society stepped in to create the Hamilton Wood Type museum.”1

In addition to the Hamilton museum, which opened in 1999, the rural industrial town also boasts a farm museum just a few streets away, which is not far from the historical ice cream parlor, tap room, and ballroom, all preserved thanks to the historical society.

But the Hamilton museum was unique in that Hamilton Manufacturing, long since sold to a new owner (the product of another ancient firm merged with a newer one), allowed the museum to coexist in the same historical factory building in Two Rivers, giving an extra hat tip to the museum’s heritage.

“I think they initially saw the museum as more of a local thing that people from the area would like to visit,” notes Moran.

But what made Hamilton’s wood type collection so great also put it at odds with the location. “You can only find so many volunteers, particularly when they have no experience with the industry,” says Moran. There wasn’t nearly enough regional interest to suitably maintain the collection. (Some former workers acted as volunteers in the museum’s early days, and a few have continued to donate their expertise. But the youngest worker when the wood-type operation shut down is well over 50 today.)

The historical society eventually appointed a director with a design background to help get the museum on track. But without any background in traditional printing, neither Hamilton’s equipment nor collection was getting any use. The warehouse began stacking up with type, which was quickly becoming unusable thanks to leaks and poor ventilation rotting the wood.

“You couldn’t come in and use the stuff. There were no regulations,” says Moran. Only a few years after it opened, “It seemed like the place was just about ready to close.”

Museum director Jim Moran.

A branding makeover

Jim Moran’s brother Bill, a designer and printer, had been volunteering at Hamilton since 2001 and made it his personal goal to try and give Hamilton more exposure. “I was just completely blown away that I grew up 40 miles away from this thing I’d never heard of until I had been a practicing designer for 10–15 years,” Bill Moran says of his interest in the museum. “Then I realized what they needed was good marketing.”

Bill, a digitizer of old fonts, was a link between eras. He was a computer guy, but taught a printing history class at the University of Minnesota. In 2002, he began to push ideas on how to increase Hamilton’s exposure to the world without changing its heart: the preservation, study, and use of wood-type letterpress printing. That began with a Web site, and then a book: Hamilton Wood Type: A History in Headlines.

“No one was talking about the place, and no one was really marketing the museum,” Bill Moran says. “There were a handful of printers from around the country going there and making beautiful type, but by 2003, it became clear that they were going to need a way to tell their story in a way that a couple paragraphs on a cool Web site wasn’t going to.” Bill is now the museum’s artistic director.

The book was a success, at least in the design community. In 2008, Jim Moran, who had grown up in his family’s printing business, took over as the new director of the museum. He had become enthralled with its history with the help of his brother’s book. Then in 2009, Kartemquin Films released Typeface, an independently produced documentary about the Hamilton museum and its challenges. The film toured the world with numerous film festivals, painting for filmgoers what seemed to be a bleak picture of the museum’s assumed fate.

“The film director told me the museum looked ‘too sad’ when I took him around,” Jim says of his days spent with the film crew. “It looked like the place was dying. And that was accurate, too, but it’s one of those things that makes the resurgence even more incredible.”

Community revitalization

Once the film was released on DVD, iTunes, and Netflix, the messages began pouring in. Jim would roll into work to find 10 new e-mails from Australia after a showing of Typeface. Then 15 new Facebook friends from Norway. Then a couple of visitors from Germany would show up. Suddenly, global interest in the Hamilton Wood Type museum looked to be trending upward.

“The film helped us an incredible amount,” says Jim. That same year, with Bill’s help and connections to the design industry, Jim began offering letterpress workshops. He wanted to make Hamilton into more than just a museum, and felt that in order to best appreciate the craft, the equipment and collection had to be in active use. Much to his surprise, the workshops became a wild success.2

“I began to get wonderful interns from Australia and England and Germany,” Jim says, highlighting the diversity of those interested in learning more about wood type. Few even knew how to make their way to Hamilton’s rural home — “I know how to get to Chicago, but how do I get to Two Rivers from there?” they would ask Jim — but they began coming in droves anyway.

Jim eventually found himself teaching a group of senior designers from Nike, and the museum even ended up partnering with Target to do a line of fall clothing that was designed and licensed from the Hamilton museum. For nearly half a year, 1,755 Target retail stores sold clothing emblazoned with images from the Hamilton museum.

The exposure helped the museum staff feel like they were finally building mind-share among modern designers. Amidst this growing interest, Thermo Fisher Scientific announced that they were moving out of their industrial building in Two Rivers, evicting the museum and leaving it to fend for itself. Bill says that wasn’t in itself bad, as the building had been let go to pot: it had severe leaking and no heat. “We had the nation’s largest collection of wood type and couldn’t protect it,” he says.

The current owners shifted the eviction date around, and zoning issues for the new location also caused worries. “There were so many unknowns as to whether they could come knocking on any given day saying we had to be out in a week. That kind of thing could have been ruinous,” Bill recalls.

Branching out

By the time the new location was settled — with help from the town — in late 2012, “We ended up having about six months to bring in 1,500 hours of volunteer time, a phenomenal outpouring of money and hours to help us make this move,” Bill says.

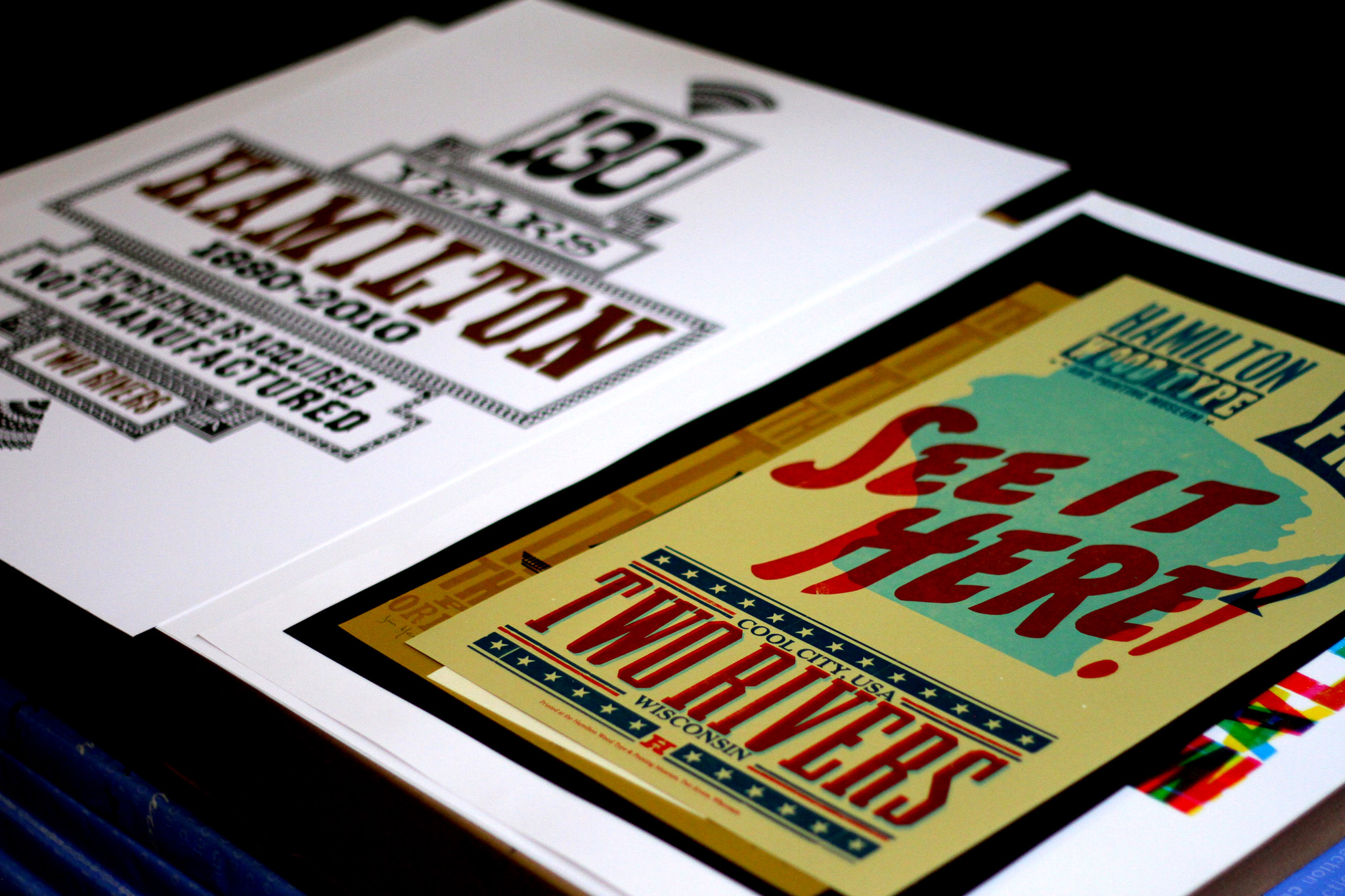

Even after the staff finished moving the massive collection, unpacking and re-organizing 26 semi-trucks’ worth of pallets, they still had not reopened the space to the public when I visited in early June. The enormous warehouse was only unpacked enough for the staff and volunteers to begin making their very first prints at the new location.

Jim, his assistant director Stephanie Carpenter, and a group of volunteers were printing posters for an upcoming conference in San Francisco at the end of June. There, they’d be showcasing some commissioned work for a client and giving talks to industry professionals about the museum and workshops. “We just can’t keep up. Demand for our work — and the workshops — is huge,” Jim says.

Indeed, part of the appeal of taking one of the $125 workshops at Hamilton is the ability to create art in practically any style using vintage equipment that’s still in active use. Those who participate in the workshops end up creating 20 to 25 prints of their own throughout the day.

Moran thinks it’s no coincidence that the uptick in participation in crafts and the do-it-yourself approach that has percolated back into culture has had a positive correlation with the revival of letterpress. Attendance at the workshops, he says, includes people who have been in the industry for a long time, but the bulk of participants are college-age graphic design students.

As that demographic continues to keep Hamilton afloat, Jim Moran now welcomes the trend with open arms. In fact, 27-year-old Carpenter only recently completed her master’s degree in graphic design from Indiana University, representing a new wave of young people interested in practicing and maintaining the craft.

Museum assistant director Stephanie Carpenter.

“There’s a 30-year difference between us, so we come at this from different angles,” Jim says. “But we both share a love of art and printing, and that’s what makes our partnership unique. And she’s a pretty good letterpress printer.”

The museum’s new location should be open to the public by August. The staff hopes to draw even more attention to its offerings through a vintage poster gallery, showcasing over 2,000 Globe printing plates from the 1920s through the 1960s, many of which were used to create successful posters for Ray Charles, Miles Davis, and historical musical venues. The Hamilton museum is now creating restrikes — or modern “mashups” — of that classic artwork.

Work cut out for it

One of Jim’s plans to help keep the museum humming, and bring in a revenue stream, is to carve and sell new wood type. He’s only aware of two other typemakers in the United States engaged in such work, making demand for the painstaking craft surprisingly high as a letterpress printing revival is underway. The Hamilton museum has carved three sets of type in recent years, including one for a 600-year-old native American language (called Lushootseed) that is on the verge of extinction.

Another was a collection the museum designed by renowned type designer Matthew Carter. Carter, in his mid-70s and a recent MacArthur Foundation fellow, has a career that spans carving metal type as one of the last youth trained in that specialty, through very early work in computer-based typesetting, and into screen fonts for Web reading. If you’ve ever seen Verdana and Georgia, you know his work.

The museum commissioned a new face from Carter in 2003, but after working on initial designs cut into templates by a former Hamilton type cutter, they were stymied by limitations in that method. In 2009, the Morans revived the project and turned to a local shop that used a CNC (computer numeric controlled) router to cut the templates directly. Carter wrote,

On the day I arrived at Hamilton I picked up a piece of maplewood type and realised that it was exactly 50 years since a type of my design had been in a physical form that I could hold in my hand.

Jim emphasizes that this is no easy (or cheap) process, but it’s worth it for a quality product. It’s the marriage of new and old methods, such as selling a rendition of Carter’s face in digital form, that permeates the museum’s revival. Despite the recent change of fortune, with a new building and a high level of outside interest, Jim and his team maintain an air of caution.

One of the main benefits to being located in the original Hamilton museum was free rent, with free light and utilities to boot — when they worked. Now, the museum holds the burden of those overhead costs. “We can support three salaries at this point and things are moving along very well,” Jim said, “but we’re still fragile.”

“I could sell all the type we could make,” Jim says. “We truly plan to get back into the business of making type. All we need are time and money.”

Photos by Jacqui Cheng.

-

Hamilton destroyed all its competitors’ font patterns after each acquisition, a decision that still causes gnashed teeth among letterpress printers today when you mention it just as if they felt it had happened a few weeks before. ↩

-

Editor’s note: Your loyal editor took a half-day course from Jim and Bill in late 2010 in Seattle, which rekindled his love of letterpress printing from the 1980s. The two are infectious about their work, and Bill has a photographic memory for names and one’s preferences for pie. ↩

Jacqui Cheng is a freelance writer, editor, photographer, and editor at large at Ars Technica. Jacqui's writing has appeared at Ars Technica since 2005 and has also been published in the Guardian, CNN, Wired, US Airways magazine, and the ebook, Unmasked. A former back-end Web developer, Jacqui's other interests include gardening, cooking, running, cycling, urban sustainability, human rights, and various forms of activism.