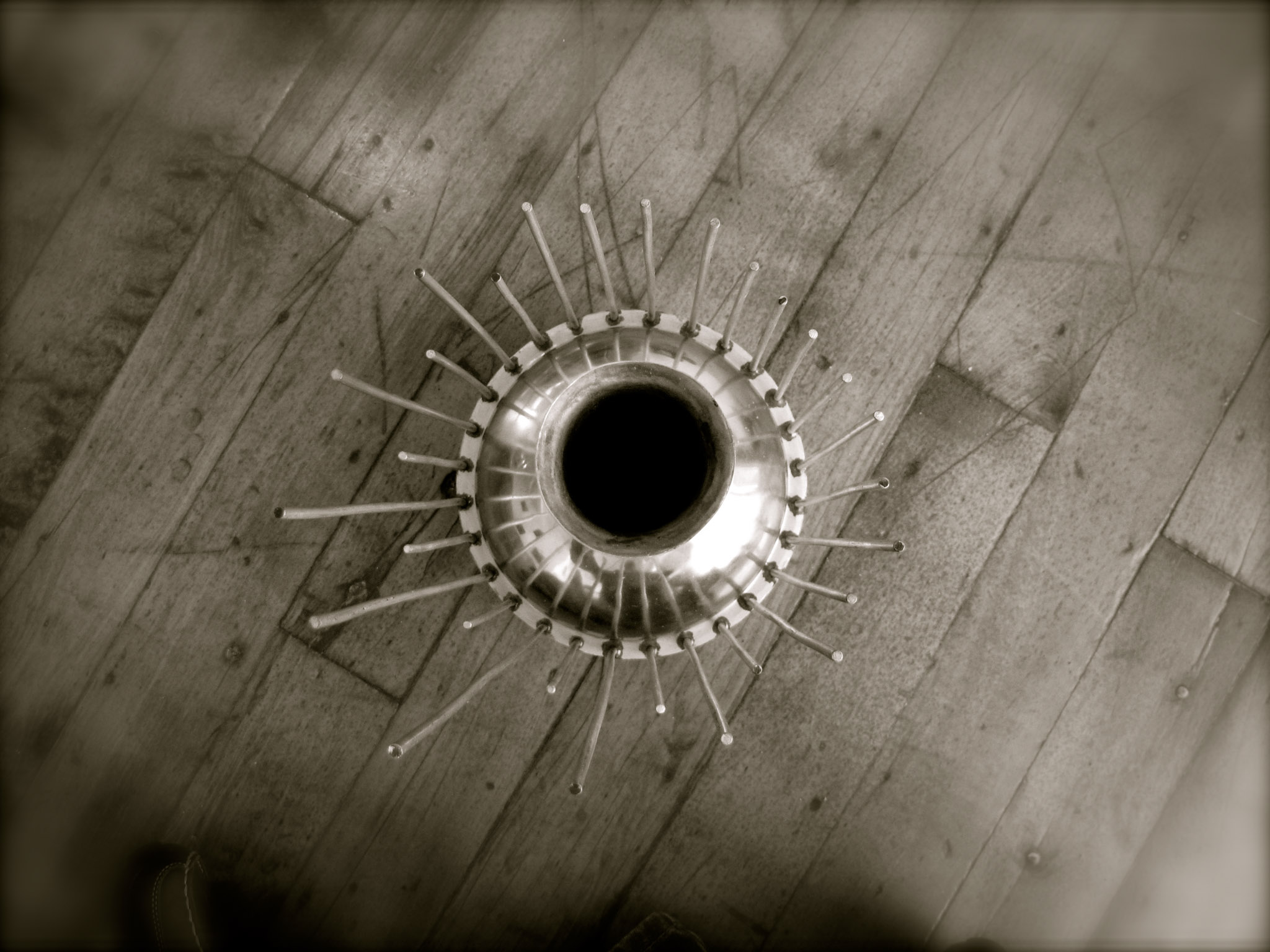

Brooks Hubbert III clutches the neck of a prickly, circular instrument that somewhat resembles an upside-down jellyfish, its tendrils represented by stiff bronze rods of various lengths. He drags a bow across a few of the rods, producing a piercing, metallic shriek. Satisfied with this, he tilts the instrument to one side, and this is where the sound goes wonky: tones bend upward, dip down, and shift sideways as the six ounces of water in the device’s base echo and resonate.

This is a waterphone, and its distinctive music is felt as much as heard — in the hair at the back of the neck; in the gut. It’s the sound of a lurching elevator or a renegade fairground ride about to spin off its axis. It might call to mind the soundtracks of 1980s-era horror and ghost movies, and with good reason. The instrument’s low, haunting moans and eerie, high-pitched squeals — like screeching brakes — have become known as the sound of suspense in films like Poltergeist, The Matrix, Star Trek: The Motion Picture, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, and Let the Right One In.

“Anyone who hears it automatically reacts to it,” says Hubbert, a 38-year-old Pensacola, Florida, musician now taking over as master craftsman after the waterphone’s creator Richard Waters died last year. “People hear the sound and they’re like, ‘Whoa, this is heavy.’ It freaks them out.”

Popular, peculiar, percussive

Invented and patented in 1969, the waterphone has captivated, confused, and generally creeped out audiences via film scores, orchestral works, and more than one experimental San Francisco concert over the past 45 years. Even as synthesizers rose to ubiquity and electronic samples could be coaxed from computers with a few deft keystrokes, Waters’ acoustic invention never lost its appeal; in times of peak demand, customers lined up for a spot on a yearlong waiting list, eager to shell out up to $1,700 for one of his handmade creations. Hubbert is now carrying on Waters’ legacy, building waterphones in his backyard workshop using the same painstaking process Waters devised.

Each waterphone starts with a stainless steel pan, shaped like two pie tins welded at the brim, which acts as a resonator. Out of this base juts a series of bronze tonal rods and a long, thick neck with an opening at the top, where the water is poured in. Fill the pan with water, and the rods vibrate and trill with woozy harmonies when tapped with a mallet or stroked with a bow. The instrument’s melody is often compared to that of the humpback whale — so much so that conservation groups have used the apparatus to summon cetaceans.

The waterphone is classified as a percussion instrument, but it has a greater range than any of its comrades in that category. There is no part of the gadget that doesn’t make music — one can strike the rods (a high-frequency melody), hit or rub the underside of the base (a chilling, low roar), or finger-drum on the neck (rain on a roof). Just don’t turn it upside down, or the water will fall out. “It fits into so many different applications because it has such a wide range of tones,” Hubbert says. “There are all kinds of playing techniques that have yet to even be discovered.”

That idea might have pleased Waters, a trained painter, kinetic sculptor, bamboo enthusiast, and lifelong creator who would often walk into a room and begin drumming on any interesting wood or brass objects he saw, according to his daughter, Rayme Waters. “He was an experimenter — he loved to just play around with metal and sound and vibration,” says Rayme, a novelist living in Palo Alto. “He was sort of tinkering toward the ideal instrument.”

An otherworldly sound

Waters’ path to invention began in grad school in the mid-1960s at Oakland’s California College of Arts and Crafts (now California College of the Arts), where he first played an instrument he described as a Tibetan water drum — a round bronze tub, filled with water, that rocked when struck. Later, dabbling in the local hippie scene, he heard the music of a kalimba in a Haight-Ashbury parade. Waters began welding his own homemade instruments out of tin cans, salad bowls, and hubcaps. He eventually showed one to his friend, jazz drummer Lee Charlton. At Charlton’s studio, the pair poured some water into the base, and the first waterphone was born.

Waters and Charlton, both drawn to experimental music, formed the Gravity Adjusters Expansion Band in 1969 and began showcasing Waters’ sonic inventions around the Bay Area. Other percussionists took notice. When drummer Shelly Manne flew up from Los Angeles and asked to buy a waterphone, Charlton knew his bandmate was onto something big. Waters soon drove a vanload of his instruments to L.A., and sold them all in one week. “It was quite the rage down there,” recalls Charlton, 81, who still has some of Waters’ original creations at his Santa Rosa home. “Every percussionist had to have a waterphone.”

Shortly after that, Hollywood came knocking. An acquaintance of Waters’ who worked as a sound-effects artist told him the waterphone had potential, and before long, composers began incorporating the instrument into film and TV scores. Thrillers were a natural fit. Think of those skin-bristling scenes where a protagonist wanders into a dark house alone — the audio accompaniment is often a waterphone. “Almost every horror or extraterrestrial or ghost movie soundtrack in the ’70s and ’80s had a waterphone, and you still hear it quite a bit,” Rayme says.

Hubbert discovered the waterphone while browsing music news on the Web in the late 1990s. “It sparked my imagination heavily,” recalls the singer and songwriter, whose tunes blend psychedelic rock, country, and bluegrass. “It inspired me to think differently about the world around me.” A sonic experimenter himself, Hubbert became intrigued by the idea of water in music and began rigging up his own inventions. He once attached a teapot to the bridge of a bass guitar for kicks.

Twelve years would pass before Hubbert could get his hands on a waterphone. He had moved back to Gulfport, Mississippi, his birthplace, and finally tracked down Waters’ phone number. It turned out that they lived in the same town. Hubbert took it as a sign. They met, talked about their shared passion for aquatic acoustics, and stayed in touch.

A few years later, Hubbert was playing a gig at a local yacht club, and Waters, not recognizing him, came up to praise the show. Hubbert took off his sunglasses and reintroduced himself; they had a fond reunion. “That opened things up for us. Once he dug what I was doing, that put us in more of a peer relationship, as opposed to me just being a weirdo fan-boy bothering him,” he recalls with a laugh.

Waters started attending Hubbert’s gigs, and Hubbert would stop by Waters’ home studio to chat about the waterphone craft. Last summer, Hubbert spent weeks writing a “musical sound painting” about a Gulf coast folk legend, using the waterphone to illustrate a hurricane in a pivotal passage. He was nearly finished when he heard Waters had died at age 77.

This was sad news to Hubbert, but he took it as another sign when Rayme Waters announced she was looking for someone to carry on the business. “Nobody else really knows how to do this,” he says. “I ended up with this sacred information. Richard had inspired me so much — I thought, ‘I kind of have to try this.’”

Fine-tuning the future

Hubbert has navigated the learning curve with gusto so far. Although he and Rayme had to reverse-engineer a few steps for which Waters left no instructions, Hubbert now produces waterphones in three sizes, employing a labor-intensive combination of welding, brazing, and meticulous tuning. Long dogged by copycat designs, Waters devised an exacting production method that he believed set his creations apart. A single waterphone can take 20 to 40 hours to fabricate, and no two sound exactly alike.

Waters’ invention has maintained a devoted player base of composers, touring percussionists, orchestras, and the occasional ritual sound healer. “It’s a beautiful instrument — it walks a treacherous line between beauty and harshness,” explains Gary Knowlton, a musician who was Waters’ next-door neighbor in Sebastopol, California in the ’90s. They held frequent jam sessions at Knowlton’s home recording studio with friends from every musical stratum, playing experimental instruments so foreign that they can’t easily be distinguished from abstract art. Tom Waits would swing by and record with them from time to time.

“The waterphone is an instrument that isn’t necessarily rhythmic or tonal,” Knowlton says. “In Western music, you usually need one or the other to get an idea of where things are going. With the waterphone, you don’t have that kind of map. In an improvisational setting, it’s another hole you can fall into, musically.”

That unpredictability is part of the appeal for Dame Evelyn Glennie, a Grammy Award-winning solo percussionist who has played the waterphone for two decades. “There are no real rules to playing it,” says the performer, based in Cambridgeshire, England. “I could let the imagination run riot and each time the instrument would speak differently. I never know how it will actually respond, and that’s one of the reasons I like it. The waterphone creates an atmosphere whereby the performer is asking the audience to come to the sound rather than the sound being handed on a plate to the audience.”

And that, Hubbert admits, is a weighty musical legacy to shoulder — but he’s up to the task. “My goal is just to carry the waterphone into the future and let it continue to inspire other people,” he says. “It’s definitely with respect and honor that I’m going forth with this.”

In fact, he envisions selling a whole series of water-filled instruments, based on his renderings of other contraptions Waters designed: a tong drum, a stringed device, and others. Ultimately, he’s hoping to introduce a new generation to the sound that changed his life. His former mentor, Hubbert believes, would approve. “It’s ‘cosmic,’ as Richard would have said.”

Photo of Brooks Hubbert III playing the waterphone by and courtesy of Nathan Dillaha. Other waterphone photos courtesy of Mike Peaslee of Soundiron.

Rachel Heller Zaimont is a Los Angeles-based freelance writer interested in animals, vegetables, and minerals. She has written for Fast Company, the Los Angeles Times, LA Weekly and other publications, and enjoys watching her cats twitch in their sleep.